Admin

Add or change a family page

All news items:

September marks Worldwide Alzheimer's Month, a time to raise awareness about a condition that affects an estimated 70,000 people in New Zealand. Dementia is a serious and debilitating condition impacting mental, social, and physical abilities. The wider public often struggles to relate to those living with dementia, leading to social isolation and loneliness for both the affected individuals and their families.

September marks Worldwide Alzheimer's Month, a time to raise awareness about a condition that affects an estimated 70,000 people in New Zealand. Dementia is a serious and debilitating condition impacting mental, social, and physical abilities. The wider public often struggles to relate to those living with dementia, leading to social isolation and loneliness for both the affected individuals and their families.

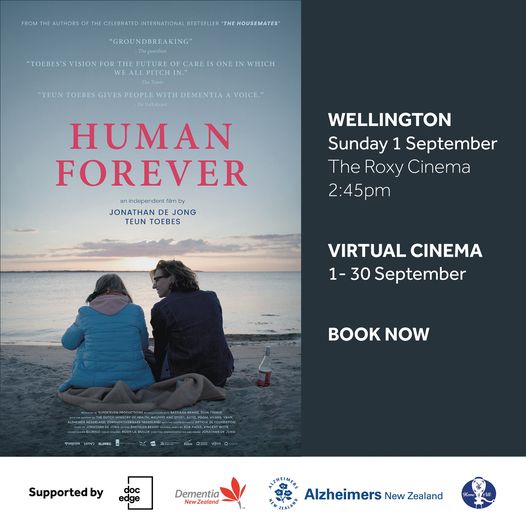

The film 'Human Forever' aims to change this narrative by showcasing how an inclusive society can be created for those affected by dementia, delivering a message of hope. It follows Care Ethics student Teun Toebes and filmmaker Jonathan de Jong as they travel the world exploring how different countries address living with dementia. Teun Toebes, who has lived in the closed ward of a nursing home for over three years, tells us: "I wanted to listen to the voices of people we have forgotten for a long time".

Jan and Marian, managers at Home4All Green Care Farm, a daycare facility for individuals in the early stages of dementia, encountered the film's producer, Jonathan de Jong, during a family visit to The Netherlands earlier this year. They learned about the film's significant impact in the Netherlands, where it received the Kristal Award for selling over 10,000 tickets. Within three months, the movie was shown in all major theaters across the Netherlands, with over 50,000 viewers to date.

Jan and Marian, managers at Home4All Green Care Farm, a daycare facility for individuals in the early stages of dementia, encountered the film's producer, Jonathan de Jong, during a family visit to The Netherlands earlier this year. They learned about the film's significant impact in the Netherlands, where it received the Kristal Award for selling over 10,000 tickets. Within three months, the movie was shown in all major theaters across the Netherlands, with over 50,000 viewers to date.

Upon returning from their trip, Jan and Marian met with the Home4All Board to discuss the possibility of bringing the film to New Zealand. They reached out to Alzheimer New Zealand and Dementia New Zealand for help with this. In order to maximize the film's impact, collaboration with those key advocates and their families was essential. Doc Edge took on the task of producing the movie in New Zealand, designating it as the film of September, Alzheimer's Month.

Though Home4All is a small organization on the Kapiti Coast, it played a crucial role in introducing this inspirational film to the New Zealand public. The film is available for viewing on the DocEdge virtual Cinema throughout September. You can view the movie trailer here.

![]()

24-year-old humanitarian activist Teun Toebes has a mission: to improve the quality of life of people living with dementia. He has been living in the closed ward of a nursing home for years when he decides to take this mission to the next level.

In 'Human Forever' he records an adventurous three-year journey across four continents and through 11 countries, taking you on a disarming and impressive quest around the world in which he looks for answers for the future.

Together with his good friend and filmmaker Jonathan de Jong, he explores how dementia is dealt with in other countries and what we can learn from each other to make the future more beautiful and inclusive. As the number of people with dementia doubles in the next 20 years, this quest is not a question, but a necessity.

"A story about love for humanity", Director Jonathan de Jong. "A must-watch for everyone who cares for elderly people or will become elderly some day."

Supported by Doc Edge, Dementia NZ, Alzheimer’s NZ and Home4All.

Premier dates:

Includes interactive Q&A with Director Jonathan de Jong and Teun Toebes after the film.

OR watch it anywhere in New Zealand through Doc Edge Virtual Cinema, from 1-30 September.

Be sure to book your tickets early to avoid disappointment: https://docedge.nz/film-of-themonth/human-forever/. Proceeds from profits made are donated to Dementia NZ, Alzheimers NZ, and Home4All.

![]()

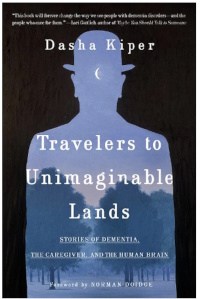

Strolling through Paraparaumu library I came across this book in the dementia section. Curious about the content I borrowed it. I more or less expected to read another helpful book on care givers' experience while caring for their loved ones with dementia. After reading the first chapter I came to realise that the contend happened to be something much more profound.

Strolling through Paraparaumu library I came across this book in the dementia section. Curious about the content I borrowed it. I more or less expected to read another helpful book on care givers' experience while caring for their loved ones with dementia. After reading the first chapter I came to realise that the contend happened to be something much more profound.

Jan Weststrate reviews Travelers to Unimaginable Lands, by Dasha Kiper

Reviewer: Jan Weststrate

To imagine what it is to care for a loved one with dementia is not just difficult, it is nearly impossible. We can only scratch the surface: how this is when we have a conversation over a cup of coffee with someone that is living with dementia. After one hour we feel exhausted and are left with more questions than answers.

To imagine what it is to care for a loved one with dementia is not just difficult, it is nearly impossible. We can only scratch the surface: how this is when we have a conversation over a cup of coffee with someone that is living with dementia. After one hour we feel exhausted and are left with more questions than answers.

Dasha Kiper, in Travellers to Unimaginable Lands, tries to explain why interacting with people that have dementia has this effect on us. Without giving too much away, she compares caring for a loved one with dementia with the Greek myth of Sisyphus, who was eternally doomed to roll a boulder up a hill only to watch it rolling down again. In a similar way, caregivers have the same experience as they forget what did not work yesterday and repeat what did not work the last time. This all adds to the frustration and pushes the love we have for our loved one to the limits.

Kiper explains how our healthy brain has evolved to automatically expect others to have the same self-reflection capacity, and to be capable of learning and absorbing new information. This is the brain's default position, which does not simply disappear when we become caregivers for people whose brains have begun to falter. One of the most difficult aspects of this is that our brain is constantly reminding us of what once was and then expecting it to function again.

The book is well written and provides plenty food for thought. It is definitely a book that a caregiver for a loved one with dementia will want to read more than once, as it inspires a sense of "I understand where you are going through". At the same time, it is brutally honest and points out the dilemma caregivers face: they have to view their loved ones as both sufficiently different from themselves and yet sufficiently familiar , so as not to lose sight of their humanity.

![]()

Volunteering as a natural remedy to postpone dementia

Some experts have argued that the interplay of social, physical and cognitive activity in later life is highly beneficial in reducing memory impairment and dementia risk. This interplay between the three typically happens in volunteering work activities. Bearing this in mind, Griep and colleagues2 set out to investigate whether this were true for seniors who do volunteering work.

Some experts have argued that the interplay of social, physical and cognitive activity in later life is highly beneficial in reducing memory impairment and dementia risk. This interplay between the three typically happens in volunteering work activities. Bearing this in mind, Griep and colleagues2 set out to investigate whether this were true for seniors who do volunteering work.

To find out, Griep and colleagues followed 1001 seniors and divided them in three groups: 1) no volunteering activities (N=531), 2) discontinuously volunteering (N=220) and 3) continuous volunteering (N=250). Their outcome measurements were 1) self-reported cognitive complaints measured by a questionnaire, and 2) likelihood receiving anti-dementia medication.

The results indicated that those retired seniors who continuously volunteered showed a significant decrease in cognitive complaints in 2012 and 2014. Also, they were less likely to be prescribed anti-dementia medication. The researchers found that those who occasionally volunteered or did not volunteer at all, could expect no decrease of cognitive complaints.

The investigators concluded that the results support the notion that retired seniors who continuously engage in voluntary work, compared to those who did not engage or who engaged only occasionally, are at lower risk for self-reported cognitive complaints and being prescribed an anti-dementia treatment.

Note: Volunteering as a senior appeared to be a natural remedy to postpone the risk of developing dementia. It also provides you with the opportunity to give positively to others in the community.

Home4All is always looking for new volunteers to assist us in creating happy days for our visitors with dementia. If you are interested in providing a happy day to those that have dementia, come and contact us at Jan@home4all.co.nz.

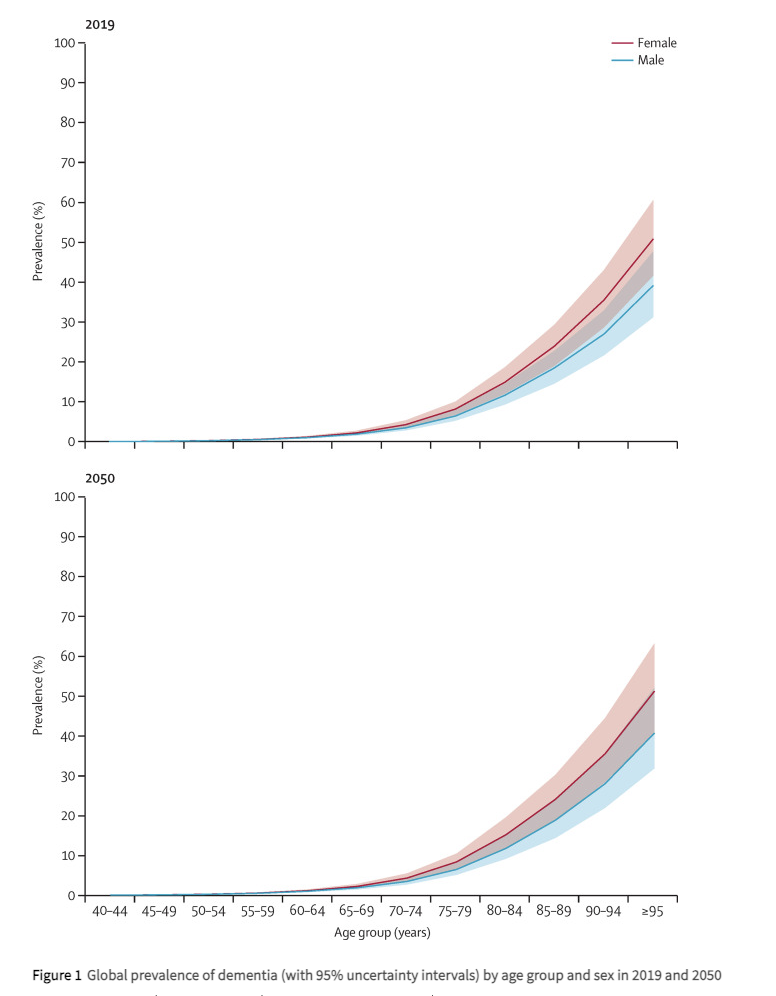

Below is a graph indicating the global prevalence of dementia by age group for male and female in 2019 and estimated figures for 20503.

![]()

Notes

1. For people aged between 65 and 69, around 2 in every 100 people have dementia. A person’s risk then increases as they age, roughly doubling every five years. This means that, of those aged over 90, around 33 in every 100 people have dementia (Source: Alzheimers.org.UK)

2. Griep Y, Hanson LM, Vantilborgh T, Janssens L, Jones SK, Hyde M. Can volunteering in later life reduce the risk of dementia? A 5-year longitudinal study among volunteering and non-volunteering retired seniors. PLoS One. 2017 Mar 16;12(3):e0173885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173885. PMID: 28301554; PMCID: PMC5354395.

3. GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022 Feb;7(2):e105-e125. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8. Epub 2022 Jan 6. PMID: 34998485; PMCID: PMC8810394.

At Home4All we focus on what you can do, rather than what you can't. It is all about creating happy days together with others, by doing the things you still can in a safe environment. We have a workshop, a vegetable garden, and animals to interact with. This short video provides an impression of some of our activities.

People living with dementia need their own government support budget

At the moment there is no government funding stream supporting this group of people. We saw this with one of the participants in the television programme "The restaurant that makes mistakes". A lady who was completely able to work in the kitchen under supervision lived in a rest home environment, where one of her biggest frustrations was that she was bored and was not able to do anything useful around the facility. It was a typical situation: too bad to stay at home alone but too good for a rest home. If she had been able to access funds that could support her staying longer at home and visiting an adult day activity centre, this would have made all the difference.

Let me introduce you to Donna[1]. Donna is a retired woman in her seventies who suffers from progressive cognitive decline/dementia and lives on her own at home. She has two sons, one who lives in New Zealand and the other in Europe. She can currently run her household but requires frequent support from her son.

Because of her cognitive decline, Donna forgets appointments and where she puts things. She is at the stage that she realises that she is forgetting, and so she frantically writes everything in her notebook in such a way that she is also unable to retrieve the information she put in it. Her finances are looked after by an agency that she visits several times per day as she forgets that she was there an hour earlier.

Three months ago, Donna came to Home4All (www.home4All.co.nz), and she spends two days per week with us. Home4All provides a safe environment for her where she does not need to be worried about what she might have forgotten. At Home4All she enjoys the company of others and can use her skills to help with the cooking and other activities around the home. This is what Donna enjoys and it gives her day meaning and fulfilment.

Unfortunately, Donna does not qualify for government support and has to pay out of her own pocket to come to Home4All. As a direct result, she has had to reduce her days coming to us from two to one day per week. As you can imagine, this again upsets her routine and puts her back into a situation full of uncertainty and social isolation.

People suffering from other neurodegenerative / life-limiting diseases are able to apply for financial support from the NZ government. This is not the case for people living with dementia / cognitive decline. We do not question whether people with cancer need support but we do for those living with dementia. Providing a variety of adult day activity programmes that enable those living with dementia to live meaningful and purposeful lives is important as it potentially reduces the slope of decline. In the UK, dementia is classified as a terminal illness[2] and therefore qualifies for the same level of care support as other life-limiting diseases receive.

Imagine if Donna could come three days per week to Home4All. We could monitor her level of decline and make sure there is appropriate care wrapped around her. We could make sure that her quality of life is as good as it can be before she dies a natural death or needs to be admitted into a care facility. Let’s not make people living with dementia wait to receive appropriate care. Give them their own care support budget to enable them to have a happy decline.

![]()

Notes

[1] To protect her identity, we changed her name.

[2] Social Care Institute for Excellence (https://www.scie.org.uk/)

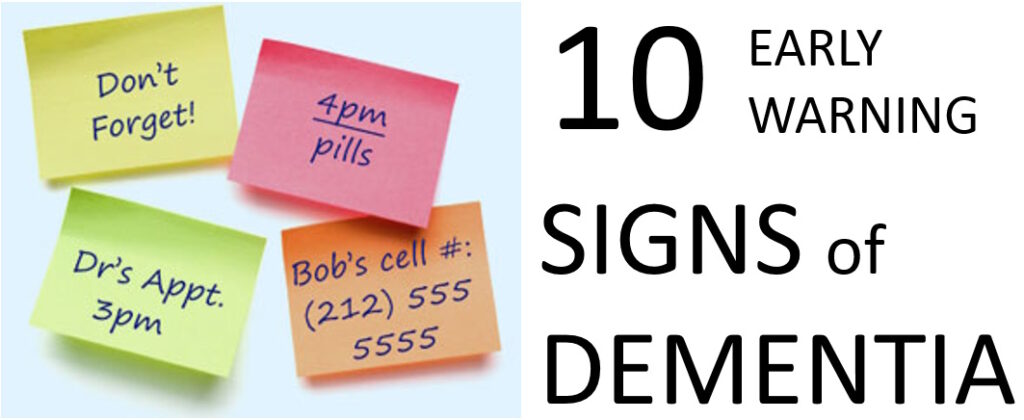

Early signs of dementia manifest differently in everyone: you can pay attention to these 10 things

Anybody who gets a day older can confirm that not everything goes as smoothly as it did when they were eighteen. Physical activities become a bit slower to complete, you get tired a bit faster, and there is a little more mental wear and tear along the way. This is a normal part of getting older, according to various international Alzheimer's and dementia organisations. What is the difference when it comes to dementia? In other words, when is being forgetful no longer innocent?

Anybody who gets a day older can confirm that not everything goes as smoothly as it did when they were eighteen. Physical activities become a bit slower to complete, you get tired a bit faster, and there is a little more mental wear and tear along the way. This is a normal part of getting older, according to various international Alzheimer's and dementia organisations. What is the difference when it comes to dementia? In other words, when is being forgetful no longer innocent?

Problems in daily life

Dementia is not a normal ageing phenomenon, but the expression of a disease. The diagnosis is made when a doctor or specialist identifies a decline in mental abilities. The decline is such that the person has difficulty with daily activities, such as getting dressed or groomed independently, cooking food, or going to the store. You cannot prevent dementia, but you can partly limit your risk by living a healthy life. According to Dementia New Zealand around 70,000 people have dementia in this country.

Researchers have known for years that long before the first symptoms of dementia appear, damage can already be found in the brain tissue of (future) patients. The underlying disease is therefore often already present before there is a problem. In addition, the first symptoms are often so subtle that it takes a long time to realise that there may be more to it. Often years pass before someone is finally diagnosed with dementia.

Sometimes memory and cognitive tests show that there is indeed a decline in mental capacity that cannot be fully attributed to the normal ageing process. However these problems are often so mild that the person in question experiences few problems in practice. Doctors then speak of mild cognitive impairment. Although this is often seen as the pre-stage of dementia, it is certainly not the case that everyone with mild cognitive impairment will actually develop dementia.

Ten signs there's more to it

There are different types of dementia, each with typical and atypical symptoms. In addition, each individual has his or her own unique experience. There is no general definition of what the first stage of dementia looks like, but the following ten symptoms are the most common.

1. Severe memory problems

Quite normal

Not being able to think of a name occasionally or forgetting when an appointment was, such things are quite normal... especially if you can remember it a few hours later.

Suspicious

One of the typical early symptoms of Alzheimer's disease is forgetting new information. People with dementia can no longer do without a calendar or other aid to remember appointments or dates because they simply can no longer store that new information in their memory. Other omens include forgetting important dates or events and asking the same question over and over again.

2. Difficulty planning and problem solving

Quite normal

If you occasionally make a calculation error or overlook an invoice, you don't have to worry immediately. It is also not abnormal that you find it more difficult to do many things at the same time as you get older.

Suspicious

Executing complex plans, for example, with many calculations is difficult and requires much more concentration than before. Typical examples are getting stuck or making mistakes when cooking or baking a recipe that you have made (successfully) often in the past. It is also suspicious if you can no longer keep track of your finances and bills when you used to be able to do so without any problems.

3. Difficulties with familiar tasks

Quite normal

Needing help with technology or figuring out how to operate another new household appliance: these are no reason to panic.

Suspicious

If someone has trouble compiling a shopping list or forgets the rules of his or her favourite game, this could be an indication that problems are starting. Forgetting the way to a place where you have been for years is also not normal.

4. Being disoriented

Quite normal

Forgetting what day of the week it is. This happens to everyone sometimes.

Suspicious

People with dementia can sometimes become disoriented in time and space. For example, he or she no longer knows what season it is or whether something happened yesterday or last week. Forgetting where one is and/or how one got there can also be an early sign of dementia.

5. Misinterpreting visual information

Quite normal

Cataracts can be the cause of blurred vision in older people, but that has nothing to do with dementia.

Suspicious

Sometimes early dementia can manifest itself in problems with vision. This concerns difficulty in estimating distance, colour or contrast and can make it difficult to read, and especially to drive.

6. Language problems

Quite normal

Don't worry if you can't find the right word for a while, but find it later.

Suspicious

Those who are or become demented may experience problems following a (one-on-one) conversation or starting a conversation. He or she repeats himself or herself within the same conversation or abruptly stops talking. It is also possible that someone with (early) dementia cannot find the right word for normal things. Instead, he or she will use a wrong word or description, for example, "hand-clock" instead of watch.

7. Losing things and not being able to find them again

Quite normal

Losing your key or wallet, but being able to think in your mind where the item might be, is quite normal.

Suspicious

People with dementia sometimes put objects in an unusual place, for example, keys in the refrigerator. Moreover, when they lose something, they are no longer able to trace where they have been or where they last saw something in order to find it again. That is why it sometimes happens that people with dementia (often in a more advanced stage) start accusing others of stealing.

8. Poor estimation or judgement

Quite normal

We all make bad decisions from time to time, such as delaying a doctor's visit when we're not feeling well or not changing the oil in our car on time. In this case, it's more about procrastination than misjudgement of the situation.

Suspicious

A sign of dementia can be that someone is less able to assess the risks or consequences of his or her actions. This manifests itself in the handling of money, for example, in spending excessively. In the area of personal care, it happens that people with dementia wear too many warm clothes on a hot day, or no longer comb their hair, et cetera.

9. Taking less initiative

Quite normal

It is not unusual that those who get older also get tired faster and sometimes just don't feel like social obligations.

Suspicious

Difficulty remembering or following a conversation can make someone with early dementia more withdrawn. They may lose interest in their previous hobbies or passions. For example, it becomes too difficult to keep following the score in their favourite rugby match.

10. Mood and personality changes

Quite normal

Being in a bad mood from time to time when something goes wrong or sticking to your own routine and way of doing things is nothing to worry about.

Suspicious

When someone feels confused, depressed, anxious or restless for no apparent reason, this could be a sign of an underlying problem.

What should you do?

When you notice one or more signs of dementia in yourself or someone close to you, it can be very confrontational. People who work in local and international dementia organisations also realise this. It sometimes seems easier to dismiss concerns than to talk about them, especially if you're worried about someone else. You may be afraid of making him or her worried or angry. Nevertheless, it is important to discuss your concerns with the doctor, so that he or she can investigate the cause of the problems and possibly propose appropriate help.

![]()

Acknowledgement

The original of this article was written by Liesbeth Aerts and published on the 3rd of August in “Algemeen Dagblad”, a Dutch newspaper. It was translated with the support of Google Translate, after which small changes were made by Home4All staff to make it relevant for a New Zealand audience.

When it comes to supporting people living with dementia in New Zealand today, day care centres play an important role. Their aim is usually twofold: to provide an engaging environment for visitors and to offer respite for their partners and/or full time care givers. This article focuses on the first aim: providing a stimulating environment.

What do people with dementia need?

People experiencing cognitive decline (dementia) tend to withdraw. They experience the world around them differently from others, and as a result are cautious to interact with people around them. They can become socially isolated which negatively affects their physical and mental health and general well-being. Day-care centres aim to reduce the impact of cognitive decline by providing social interaction, physical exercise and mental engagement. Most centres offer activities such as games, music, quizzes, storytelling, physical exercise, creative expression, eating together and the like.

The truth is, this model does not work for every person experiencing cognitive decline. People living with dementia want to live a purposeful life just like the rest of us which will vary from person to person. Some do like games or having a conversation, others prefer to be outside and be involved with day to day things as much as they are still able to.

Home4All wants to provide a model focusing on **empowering** people living with dementia. A recent study (1) identified four aspects important to empower people with cognitive decline / dementia:

- Having a sense of personal identity

- Having a sense of choice and control

- Having a sense of usefulness and being needed

- Retaining a sense of worth

Obviously these four aspects of empowerment can only be addressed taking into consideration the stage of cognitive decline the person is in.

At Home4All, our aim is to empower our visitors (people experiencing mild to moderate dementia) to use their lifelong skills, by engaging them in day-to-day activities they enjoy and can carry out with (or without) support from others. The ‘farm type’ environment consists of a large property (~200m2) set in a residential area with lawns, a flower garden, vegetable garden, large workshop (60 m2), several chickens and a dog. We support 8-10 people in their dementia journey and aim to give them the best experience of the week.

Ian – a problem solver, proud of his successes

Knowing and acknowledging who people are, empowers them to be confident in their identity. One of our visitors, Ian, is a born problem solver. Talk about a problem and he will immediately come up with solutions. For example, when we remove the nuts and bolts from the crossbars some of those are very hard to undo. Ian will always find a way to get it done and is ever so proud when he succeeds. A couple of these moments during the day let him go home with a smile on his face, telling us he had a good day.

Offering a choice is often challenging for people living with dementia. They do not want to make mistakes, as this is what they experience often in the early stage of cognitive decline. Presenting them with too many options creates confusion - it helps to narrow things down to a few more manageable choices for the person to choose from.

Kaye – choosing activities with happy memories

Why people make certain choices is not always clear from the get-go, but you might discover the reason along the way. One of our visitors, Kaye, is naturally cautious about making a choice if different options are presented. Recently I asked him to choose from a range of activities, one of them was digging a section of the vegetable plot. He is an 82-year-old fit gentleman and to my surprise he chose the digging. Digging is physically exerting, so we stayed close to make sure he was alright. After an hour he was still digging and appeared to enjoy himself. When I asked him why he enjoyed the digging (as he had an office job all his life), he mentioned it brought back happy memories of working as a child with his dad in the vegetable garden.

Having a sense of usefulness and being needed empowers people living with dementia. Like us, people living with dementia want to be useful to the people around them. Excluding them from activities that lie within their ability does not benefit their wellbeing. Especially normal day to day activities like laying the table and being involved in the washing up are a great way to make them experience reciprocity.

Chris* – an eye for detail and a sense of achievement

Activities that preserve their skills and talents is another great way to achieve this. Sometimes we need to encourage them, as they “forget” they still have those skills and talents. One of our visitors, an emeritus academic, took great satisfaction in ordering materials for the workshop like screws and bolts etc. This reflected his academic process in the past of ordering and analysing data and he applied his eye for detail to make sure the materials were exactly what was needed. He was very pleased to see everything neatly organised in one of the storage boxes - this gave him a great sense of achievement.

When it comes to the theme of retaining a sense of self-worth this is often challenged by their level of insecurity. People around them tend to take over and make decisions for those living with dementia. This can be frustrating and undermine their confidence.

Dave – feels valued for his mechanical skills

One of our visitors, Dave, was a mechanic all his life and loves to mess around with appliances and machines. When Dave comes to Home4All we try to have an appliance for him that he can take apart. While doing this, we notice that old skills and insights surface like asking for a special tool to do the job, a tool we had never even heard of. At the end we thank him for doing such a good job and confirm his expertise was needed to get the job done. When he goes home in the afternoon, he mentions he’s had a perfect day; although he does not remember exactly what he has done, he does remember feeling valued.

There are many more examples that we can give of our visitors responding positively to the environment we place them in. At Home4All we aim to create a natural “farm” type environment which provides a variety of activities visitors can choose from. The environment challenges them and provides them with self-worth and dignity. We only offer support when they need it and, miraculously, those occasions are far less than we expect. We know their dementia cannot be reversed but we can increase the level of satisfaction, self-worth and well-being of our visitors by empowering them.

![]()

Literature

- van Corven CTM, Bielderman A, Wijnen M, Leontjevas R, Lucassen PLBJ, Graff MJL, Gerritsen DL. Defining empowerment for older people living with dementia from multiple perspectives: A qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021 Feb;114:103823. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103823. Epub 2020 Nov 10. PMID: 33253930.

* Names have been changed to protect people’s privacy.

Lying awake for hours, tossing and turning, worrying, having satisfactory, pleasant and sufficient sleep is sometimes a problem for all of us, let alone someone with dementia, who recognizes their environment less and less, who exchanges day and night rhythm and has little to do during the day. But what exactly are sleeping problems, and how do you achieve good care?

Health Behavioural Registered Nurse Koen Manders has developed The Sleep Method, a step-by-step guide for a qualitatively better night's sleep.

One of the most important reasons for admission to a nursing home is issues with sleep: nocturnal restlessness, sleeping problems, or a caregiver who can no longer handle the care (at night). Unfortunately, sleeping medication, such as Temazepam, or a tranquilizer, such as Oxazepam, are still readily used. This has to change. The Dutch Care and Coercion Act* (abbreviated as WZD) also requires this.

One of the most important reasons for admission to a nursing home is issues with sleep: nocturnal restlessness, sleeping problems, or a caregiver who can no longer handle the care (at night). Unfortunately, sleeping medication, such as Temazepam, or a tranquilizer, such as Oxazepam, are still readily used. This has to change. The Dutch Care and Coercion Act* (abbreviated as WZD) also requires this.

It is known that sleep has a restorative function, both for the body and for brain activity. Cognitive processes, including memory and concentration, are given the chance to recover and 'reset'. Furthermore, it is not yet fully known what the purpose of sleep is. Three processes that affect sleep are:

- Biological clock (circadian rhythm): this nucleus in the hypothalamus regulates, through hormone levels, a recurrent structure of sleep and wake of approximately 24 hours.

- Sleep rhythm: sleep is not a fixed state, but a rhythm that lasts from 90 to 120 minutes, in which various brain activities take place. This can be roughly divided into deep sleep, light sleep and REM sleep (dream sleep).

- Sleep demand: The need for sleep increases during the day and decreases again during the night.

Long-term disruption of sleep can lead to many complaints. Symptoms such as cardiovascular disease, obesity, depression or anxiety can arise. It also affects one’s mood, concentration and memory reduced autonomy and independence can occur. If this happens occasionally, it likely isn’t cause for concern. If this is a regular occurrence, it may be an issue, especially if it is recurring for several nights in a row.

As age progresses, so-called gerontological changes occur in and around sleep:

- Biological clock (circadian rhythm): the hormone levels and body temperature linked to the sleep and wake cycle become less apparent. The number of consecutive hours of sleep at night decreases and the need for a nap during the day increases.

- Sleep rhythm: sleep becomes less deep, and sleep remains more in light sleep and REM sleep. There is also more change between the phases, and the rhythm is no longer constant.

- Sleep demand: demand builds up faster and is more difficult to release during the night.

Sleep hygiene

A good night's sleep starts during the day. A few tips to help achieve this are:

• A quiet and dark bedroom

• Keep screens (such as tablet, smartphone, television, etc) out of bedroom

• Make sure to only do relaxing activities, such as reading, at least an hour before bedtime

• Avoid caffeinated and alcoholic drinks several hours before bedtime

• Schedule a moment of worry during the day to come up with solutions to problems

• Refrain from eating heavy meals in the hours before bedtime

• Exercise regularly, but no later than three hours before bedtime

• Ensure an environment with sufficient light during the day

• Avoid naps or power naps during the day

• Try to get up at exactly the same time every day, even on weekends

The first intervention for sleeping problems is often the use of sleep medication. This entails many risks. The cognitive impairments as a result of dementia are additionally enhanced, as are daytime fatigue and an increased risk of falls. In addition, medication is also known to block the restorative functions of sleep, so that someone can relax, but this, for example, makes it more difficult to process difficult experiences. The Care and Coercion Act (WZD) has been developed to protect clients against unnecessary and unsafe use of these substances. The WZD regulates involuntary care for clients with dementia. This includes the use of behaviour-influencing medication and freedom restricting treatments , such as the closed door, bed rails or the weighted blanket. ?The basic principle is that the situation is looked at in a multidisciplinary way, whereby mainly sought for alternatives; is short terms: No… unless. ?

The search for alternatives is central to the WZD. Involuntary care may only be used if it can be demonstrated that sufficient alternatives have been investigated. But what are the alternatives? For the night, people often think of an extra low bed, or extra supervision, for example in the form of an infrared sensor, are sufficient, but there is no suitable guideline to answer these questions. Apart from sleep hygiene (see box), there is therefore no ready-made answer to sleeping problems. The night situation is different for everyone, including clients with dementia. This is why it is good to systematically search for suitable solutions geared to the individual patient’s needs.

The sleeping position

Everyone has a different position in bed. One prefers to sleep on their stomach, and another changes position every half hour. In hospitals, patients are traditionally placed on their backs in bed, so that the nurses can easily reach everything. Moreover, this is a healthy posture for the body. This preference of care employees is also reflected in home care or in a nursing home. That is what is taught in training. However, if someone has trouble changing their posture due to apraxia or physical problems, but prefers to sleep on their right side, it can be a long night.

The Sleep Method is to help you find suitable solutions. It is a method that analyzes the sleeping situation on the basis of six steps and offers solutions to help the personal situation. Literature, studies and various practical experiences form the basis of the method, which bundles numerous interventions and divides them over the various steps. The method has been developed to offer alternative solutions. This gives care workers, informal caregivers and specialists a chance to look more broadly at the preferences of the client, and gives the opportunity to think of what might suit the individual client. In this way, customization and a person-oriented solution can be offered to the client with sleeping problems. The request from the WZD is also met with opportunities to take a broad look at alternatives and to only proceed with involuntary intervention only when these alternative options have been exhausted.

The sleep history is the basis of the sleeping method. In this first step, information is collected that can be used to identify which sleeping problems there are, and which solutions or interventions can be linked to these in the later steps. This is done, among other things, with a sleep/wake calendar, supplemented with questionnaires for the client, caregiver or care staff. This step is seen as a baseline measurement.

The sleep history is the basis of the sleeping method. In this first step, information is collected that can be used to identify which sleeping problems there are, and which solutions or interventions can be linked to these in the later steps. This is done, among other things, with a sleep/wake calendar, supplemented with questionnaires for the client, caregiver or care staff. This step is seen as a baseline measurement.

In step 2, we first look at various possible causes. Based on the information collected during the observation phase, together with the involved disciplines, such as occupational therapist, doctor and home care, we look at issues that may underlie poor sleep. These could be issues such as:

• Pain

• Itches

• Posture or discomfort

• Incontinence problems

• Sleep disorders

• Medication

Or any other number of physical causes.

This step, together with step 4, is the most important step within the Sleep Method. The aim is to look at the individual situation and to have it match the client's needs better. This is especially important, especially when admitted to a nursing ward, though it can also provide surprising solutions and ideas to the home situation. The sleeping climate and the preconditions can already be enough to stimulate a good night's sleep. These are a few things you may want to consider:

• Bedtime routines

• Bed linen and own pillow

• Nightwear

• Decoration and furniture of the room

• The temperature of the room. Elevated skin temperature is associated with drowsiness, deeper sleep and less frequent waking. This is why it is important to ensure you have a cool environment and warmth under the covers.

Every client is different, and the interventions are different for every client. This is why it is impossible to list all possible interventions. However, it is important to let go of one's own values and preferences and to look with an open mind at the client and their preferences, however small or strange they may be.

Alternative interventions include the use of signposting, dynamic stimuli, light therapy, day structure, and many other options that promote good sleep. In this step we look for appropriate interventions that can be added to the personal situation surrounding the client.

One form of a dynamic stimulus is a musical pillow. This pillow offers music or sound close to the head so that the client is distracted from sounds and ensures less of the desire to get up and be distracted by these sounds. The purpose of signage is to make it more visible where a client can find the toilet, for example. This can be done, for example, with illuminated arrows, or an image of the toilet on the outside of the bathroom door.

A recognizable daily rhythm is also important. A good variety of activity and rest matches the sleep needs of the elderly. In addition, this ensures recognisability and the client is less likely to withdraw or become bored.

If there is enough variety, an activity can also be offered in the evenings. A nice bath, something to eat while watching television or a game. This ensures that the time at which the older person goes to bed shifts and so does the time of waking up in the night. A win-win situation.

The last two steps concern the use of signals, and influence the freedom of movement or the use of sleep medication. With all these resources, it is important to take the considerations of the WZD into account and to compare these results. Sometimes a situation calls for the deployment of involuntary care, for example, if the client cannot find peace at night. Medication can sometimes offer a short-term solution, but also consider options that affect freedom of movement, such as a ball blanket, a tent bed, bed rails or an extra low bed. If a client cannot get out of bed by themself, the bed imposes a restriction. If a client cannot get up from the extra low bed, the complete step-by-step plan of the WZD must be followed, as this amounts to a restriction to the freedom of movement.

Sleep medication is only included in the method as a last resort. For some clients, this is a godsend, but there are few resources that actually offer better quality of sleep. The effect of medication is mainly to stun the client. Sleep medication can offer a temporary solution to, for example, stabilize the day and night rhythm again. That is why the means are mentioned and included in the sleeping method. Sleep medication always falls under the means that influence behaviour and the complete step-by-step plan of the WZD must always be followed for this to be taken into consideration.

While going through the steps, various disciplines can be consulted, such as an occupational therapist, family doctor, nurse and home care. The support of a dementia case manager / adviser can also help with this. They can all think along and supplement when you get stuck as a care professional, informal carer or client.

Author: Koen Manders

Website: www.kmconsulatatie.nl

kmconsulatatie@outlook.nl

Translation: Google, J. Weststrate, H. Cunningham

First published in: Denkbeeld February 2022

Picture: YUMMYBUUM/ADOBESTOCK

* Note: The Dutch Care and Coercion Act differs from the New Zealand legislation.

Bell mat

The bell mat is an example of a signal that can be used at night. This mat is available in different variants:

• in bed under the bottom sheet or under the mattress to receive a signal when the client moves more or less

• as a mat on the floor next to the bed. If the client stands on this, the care worker receives a signal. They can then consider whether the client needs assistance and offer guidance if necessary. This aid can also be used during the day when the client is sitting in a chair in his room.

“This is how I want to live if I were to develop dementia!” When I was young one of my favourite TV programmes was “Swiebertje”. When I have a dull moment nowadays I go and find an episode of “Swiebertje” on YouTube. Watching it brings me right back to the excitement I had watching it when I was 8 years old. I can still laugh about the funny situations and the hilarious conversations. Watching “Swiebertje” lifts my mood. I am definitely including it in my Dementia Passport.

“This is how I want to live if I were to develop dementia!” When I was young one of my favourite TV programmes was “Swiebertje”. When I have a dull moment nowadays I go and find an episode of “Swiebertje” on YouTube. Watching it brings me right back to the excitement I had watching it when I was 8 years old. I can still laugh about the funny situations and the hilarious conversations. Watching “Swiebertje” lifts my mood. I am definitely including it in my Dementia Passport.

Dementia passport

By Jan and Marian Weststrate

Yes, it is true that around 1 in 5 women, and 1 in 10 men will develop dementia at some point in their life (source Alz.org). In New Zealand one in four people die with this disease. This underscores the importance of being prepared and taking proactive steps to manage the condition.

One way to prepare for dementia is by creating a Dementia Passport in case you develop dementia. A Dementia Passport is a document that contains important information about you as a person. It focuses not so much on the medical side but much more on what you deem to be important in your life and enjoy, so that, if you develop dementia and are unable to communicate your preferences, the passport provides that information to those that care for you.

Your passport tells others what music you like; what your morning and evening routine is like; what conversations you enjoy (and don’t enjoy) and what television programmes you like to watch, particularly those ones when you were young. Next, is to list your favourite smell or which smells absolutely upset you (e.g. overripe bananas). It can also include how much you want to be involved with others and what time of the day you would like to be on your own. It is also important to include what embarrasses you, and what kind of situations you want to avoid. Don’t forget to include the type of books you like to read, or have read to you, when you are unable to read anymore. As you can see, you can add many aspects of your life to your Dementia Passport.

Creating a Dementia Passport can help ensure that when you develop dementia you receive appropriate person-centred care, even if you are unable to communicate your needs and preferences. Your passport can also help minimize confusion or misunderstandings among healthcare providers and caregivers, and can provide peace of mind to family members and loved ones.

To create a Dementia Passport, it is recommended to involve your loved ones and closest family. They probably know you better than anyone. You can always ask a dementia specialist to read it afterwards and ask him/her if it all makes sense. They can help ensure that the passport includes all relevant information and that it makes sense to others that do not know you. It is also important to keep your Dementia Passport up to date, and to review it regularly (e.g. yearly) as new things might pop up that you want included.

With one in five to ten people developing dementia, it is better to be safe than sorry on this topic.

Editorial note from Home4All

The Dementia Passport was initially suggested by Evelien Tonkens, professor of Citizenship and Humanization of the Public Sector at the University of Humanistic Studies in Utrecht, The Netherlands. She suggested this on 7/1/2007 in a column in The Volkskrant (a Dutch newspaper).