Admin

Add or change a family page

All news items:

We invite you to join us for a very special theatrical experience, as the award-winning play In Other Words graces the stage at Circa Theatre for a limited season from 27 February to 8 March 2025.

We invite you to join us for a very special theatrical experience, as the award-winning play In Other Words graces the stage at Circa Theatre for a limited season from 27 February to 8 March 2025.

In Other Words tells the poignant story of Arthur and Jane, whose enduring love faces the challenge of Alzheimer's.

This is a unique chance to witness the extraordinary talents of acclaimed acting couple Jennifer Ward-Lealand and Michael Hurst, as they come together for the first time in a captivating double performance.

More: https://www.circa.co.nz/package/in-other-words

In this poignant narrative, which underscores the complex emotional landscape faced by families dealing with dementia, a husband welcomes his wife back home for the first time since her admission to a local rest home's dementia ward. Despite his frequent visits to the nursing facility, the homecoming marks a significant moment in their journey. The story sheds light on the inevitable emotional distance that dementia creates between loved ones. The husband's struggle to reconcile with the presence of this "new" person in their shared space is palpable. Ultimately, the act of bringing her home serves more as a gesture for the person with dementia than for the husband himself, illustrating the profound challenges that accompany this relentless condition.

Back home for a short while

How did we come up with the idea? My wife needed to go to the hairdresser, which was near the place we had lived for over twenty-five years. A good opportunity, suggested my youngest daughter, to let her come home again. After all, it had been half a year since she was admitted to a nursing home.

How did we come up with the idea? My wife needed to go to the hairdresser, which was near the place we had lived for over twenty-five years. A good opportunity, suggested my youngest daughter, to let her come home again. After all, it had been half a year since she was admitted to a nursing home.

Early in the afternoon, my wife and daughter clattered up the stairs. I was delighted, but at the same time tense: could something happen that we hadn't foreseen? One of her carers had assured me that it couldn't hurt unless I made a habit of it – which I wasn't planning to do.

“Well, here we have Mrs Abrahams, come in,” I called with ironic solemnity as she took the last steps. She gave me a smile, kissed me quickly, and walked into the hallway, where she immediately started looking at some artworks on the walls. Then she stepped into the living room with us. She said little and looked around with a neutral gaze, like someone visiting for the first time and cautious of making a pronounced judgement.

Then she also approached the walls here to take a closer look at the paintings and etchings. They met with her approval, especially if they depicted cats – and there were quite a few, partly thanks to her influence. “Look at that cat! Beautiful!” She pointed enthusiastically at a cat sitting alone in a cluttered living room with a view of an empty meadow in a coloured pencil drawing by Roos de Lange. Cats are often lonely, Roos de Lange must have thought.

Then she stood for a long time in front of a large painting which she had looked upon daily from the sofa, for about fifteen years. The painting was by Lili Freriks,and showed a cat lying stretched out asleep in the glow of a large lampshade. She was almost speechless with admiration; she had never seen anything so beautiful before.

That applied to everything, even the stone figurines of cats she had collected and now held lovingly in her hands. There was, curiously enough, one exception: the serene portrait of a German or Austrian woman from the thirties. “Looks familiar,” she muttered.

It was the only sign of recognition in the few hours she spent with us. The living cat in our house, which she had known for about five years, was observed with surprise: “A cat!”

It was as if she was walking around in an unfamiliar museum, a place for passers-by, with me as the gallery attendant. Yet she had mainly furnished this museum herself, largely according to her taste and sense of arrangement.

We sat together for a few relaxed hours. Small talk. The conversation went in all directions, except that of coherence. We had become accustomed to that by now. Dementia does not follow straight paths, only winding ones that end somewhere in a dense fog.

The end of the afternoon went smoothly. I had anticipated that she might resist leaving, but that was not the case. We suggested taking a little walk and brought her back to the nursing home, where dinner awaited.

Tomorrow she would have forgotten it all again, but today she enjoyed it.

The author, Frits Abrahams, is a columnist for NRC, a Dutch newspaper. His wife has dementia and was admitted into full-time care six months ago. The text above has been adapted for a New Zealand audience. The original text was published in the NRCV edition on the 19th of February, 2025.

I recently came across this touching story in the Dutch magazine DementieVisie, in which a person suffering from dementia called Martin (aged 86) speaks from the heart in describing how he feels about his gradual losses in the battle with dementia, and how he tries to stay positive and manage the process.

"I'm so afraid of that slippery slope," Martin says. He finds it difficult to accept that he can no longer do so many things that he used to do.

Words from the heart

"I don't believe I have dementia. If there were signs of dementia, I would notice it, right? That's how I think. At the same time, I do realize that I'm declining and I can't do lots of things anymore. I'm afraid of being labelled. I associate dementia with childishness, I suppose. It makes me think of someone who can't do simple things, is confused, and I don't see myself like that. I recently had a fall and hurt my back, I noticed that more. I became slower at thinking and making decisions. I get really annoyed by that. I can't get used to it. I think my brain was shaken by that blow, and that's why I can't think normally anymore. You're 86, right? Sometimes I'm just in denial, other times I think: 'how annoying I have to go through all this'."

"Dementia is a horrible word; it represents something nobody wants. I'm afraid of going downhill, that I will no longer be able to think the way I used to. I don't care that I can't run so fast anymore. I sometimes compare it to the past — I was always the slow coach in the football club at Rotterdam. You know what? I like to go against the grain; I'm someone who doesn't blindly accept anything. Maybe my resistance comes from stubbornness; I can't accept that I can't do certain things anymore. I like to be direct. I like to say what I think, in polite terms. Rough on the outside, soft on the inside."

"Stay optimistic. I think exercise is very important because it provides oxygen to the body and promotes health. Being positive is the second thing that helps a lot. If you have a negative character, and don't notice the pleasures of life, and don't want to do fun things anymore, then you go backwards. Oh, who am I? I am a simple boy from Rotterdam who did not study psychology, but I am still convinced that you live longer if you have an optimistic character. If you participate in positive things, and keep up with new developments. All these things help frm a basis for positive thinking."

"Let go. Release the reins. I have to say goodbye to the idea that there is nothing wrong with me. Because there is something wrong. Being less capable is a natural process, but I mourn everything I'm losing. I find it difficult to look at things positively now, while I always did before. I'm going to try and accept the fact that I'm no longer that football player from Rotterdam and focus on what is possible. Letting go of the reins would give me a chance to still be in control but with less tension.

These words were recorded by Lies Orthmann, editor of DementieVisie. Lies works as a manager in mobile geriatric care.

September marks Worldwide Alzheimer's Month, a time to raise awareness about a condition that affects an estimated 70,000 people in New Zealand. Dementia is a serious and debilitating condition impacting mental, social, and physical abilities. The wider public often struggles to relate to those living with dementia, leading to social isolation and loneliness for both the affected individuals and their families.

September marks Worldwide Alzheimer's Month, a time to raise awareness about a condition that affects an estimated 70,000 people in New Zealand. Dementia is a serious and debilitating condition impacting mental, social, and physical abilities. The wider public often struggles to relate to those living with dementia, leading to social isolation and loneliness for both the affected individuals and their families.

The film 'Human Forever' aims to change this narrative by showcasing how an inclusive society can be created for those affected by dementia, delivering a message of hope. It follows Care Ethics student Teun Toebes and filmmaker Jonathan de Jong as they travel the world exploring how different countries address living with dementia. Teun Toebes, who has lived in the closed ward of a nursing home for over three years, tells us: "I wanted to listen to the voices of people we have forgotten for a long time".

Jan and Marian, managers at Home4All Green Care Farm, a daycare facility for individuals in the early stages of dementia, encountered the film's producer, Jonathan de Jong, during a family visit to The Netherlands earlier this year. They learned about the film's significant impact in the Netherlands, where it received the Kristal Award for selling over 10,000 tickets. Within three months, the movie was shown in all major theaters across the Netherlands, with over 50,000 viewers to date.

Jan and Marian, managers at Home4All Green Care Farm, a daycare facility for individuals in the early stages of dementia, encountered the film's producer, Jonathan de Jong, during a family visit to The Netherlands earlier this year. They learned about the film's significant impact in the Netherlands, where it received the Kristal Award for selling over 10,000 tickets. Within three months, the movie was shown in all major theaters across the Netherlands, with over 50,000 viewers to date.

Upon returning from their trip, Jan and Marian met with the Home4All Board to discuss the possibility of bringing the film to New Zealand. They reached out to Alzheimer New Zealand and Dementia New Zealand for help with this. In order to maximize the film's impact, collaboration with those key advocates and their families was essential. Doc Edge took on the task of producing the movie in New Zealand, designating it as the film of September, Alzheimer's Month.

Though Home4All is a small organization on the Kapiti Coast, it played a crucial role in introducing this inspirational film to the New Zealand public. The film is available for viewing on the DocEdge virtual Cinema throughout September. You can view the movie trailer here.

![]()

24-year-old humanitarian activist Teun Toebes has a mission: to improve the quality of life of people living with dementia. He has been living in the closed ward of a nursing home for years when he decides to take this mission to the next level.

In 'Human Forever' he records an adventurous three-year journey across four continents and through 11 countries, taking you on a disarming and impressive quest around the world in which he looks for answers for the future.

Together with his good friend and filmmaker Jonathan de Jong, he explores how dementia is dealt with in other countries and what we can learn from each other to make the future more beautiful and inclusive. As the number of people with dementia doubles in the next 20 years, this quest is not a question, but a necessity.

"A story about love for humanity", Director Jonathan de Jong. "A must-watch for everyone who cares for elderly people or will become elderly some day."

Supported by Doc Edge, Dementia NZ, Alzheimer’s NZ and Home4All.

Premier dates:

Includes interactive Q&A with Director Jonathan de Jong and Teun Toebes after the film.

OR watch it anywhere in New Zealand through Doc Edge Virtual Cinema, from 1-30 September.

Be sure to book your tickets early to avoid disappointment: https://docedge.nz/film-of-themonth/human-forever/. Proceeds from profits made are donated to Dementia NZ, Alzheimers NZ, and Home4All.

![]()

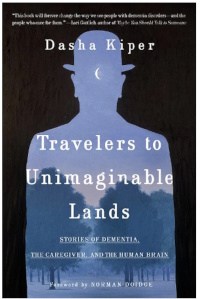

Strolling through Paraparaumu library I came across this book in the dementia section. Curious about the content I borrowed it. I more or less expected to read another helpful book on care givers' experience while caring for their loved ones with dementia. After reading the first chapter I came to realise that the contend happened to be something much more profound.

Strolling through Paraparaumu library I came across this book in the dementia section. Curious about the content I borrowed it. I more or less expected to read another helpful book on care givers' experience while caring for their loved ones with dementia. After reading the first chapter I came to realise that the contend happened to be something much more profound.

Jan Weststrate reviews Travelers to Unimaginable Lands, by Dasha Kiper

Reviewer: Jan Weststrate

To imagine what it is to care for a loved one with dementia is not just difficult, it is nearly impossible. We can only scratch the surface: how this is when we have a conversation over a cup of coffee with someone that is living with dementia. After one hour we feel exhausted and are left with more questions than answers.

To imagine what it is to care for a loved one with dementia is not just difficult, it is nearly impossible. We can only scratch the surface: how this is when we have a conversation over a cup of coffee with someone that is living with dementia. After one hour we feel exhausted and are left with more questions than answers.

Dasha Kiper, in Travellers to Unimaginable Lands, tries to explain why interacting with people that have dementia has this effect on us. Without giving too much away, she compares caring for a loved one with dementia with the Greek myth of Sisyphus, who was eternally doomed to roll a boulder up a hill only to watch it rolling down again. In a similar way, caregivers have the same experience as they forget what did not work yesterday and repeat what did not work the last time. This all adds to the frustration and pushes the love we have for our loved one to the limits.

Kiper explains how our healthy brain has evolved to automatically expect others to have the same self-reflection capacity, and to be capable of learning and absorbing new information. This is the brain's default position, which does not simply disappear when we become caregivers for people whose brains have begun to falter. One of the most difficult aspects of this is that our brain is constantly reminding us of what once was and then expecting it to function again.

The book is well written and provides plenty food for thought. It is definitely a book that a caregiver for a loved one with dementia will want to read more than once, as it inspires a sense of "I understand where you are going through". At the same time, it is brutally honest and points out the dilemma caregivers face: they have to view their loved ones as both sufficiently different from themselves and yet sufficiently familiar , so as not to lose sight of their humanity.

![]()

Volunteering as a natural remedy to postpone dementia

Some experts have argued that the interplay of social, physical and cognitive activity in later life is highly beneficial in reducing memory impairment and dementia risk. This interplay between the three typically happens in volunteering work activities. Bearing this in mind, Griep and colleagues2 set out to investigate whether this were true for seniors who do volunteering work.

Some experts have argued that the interplay of social, physical and cognitive activity in later life is highly beneficial in reducing memory impairment and dementia risk. This interplay between the three typically happens in volunteering work activities. Bearing this in mind, Griep and colleagues2 set out to investigate whether this were true for seniors who do volunteering work.

To find out, Griep and colleagues followed 1001 seniors and divided them in three groups: 1) no volunteering activities (N=531), 2) discontinuously volunteering (N=220) and 3) continuous volunteering (N=250). Their outcome measurements were 1) self-reported cognitive complaints measured by a questionnaire, and 2) likelihood receiving anti-dementia medication.

The results indicated that those retired seniors who continuously volunteered showed a significant decrease in cognitive complaints in 2012 and 2014. Also, they were less likely to be prescribed anti-dementia medication. The researchers found that those who occasionally volunteered or did not volunteer at all, could expect no decrease of cognitive complaints.

The investigators concluded that the results support the notion that retired seniors who continuously engage in voluntary work, compared to those who did not engage or who engaged only occasionally, are at lower risk for self-reported cognitive complaints and being prescribed an anti-dementia treatment.

Note: Volunteering as a senior appeared to be a natural remedy to postpone the risk of developing dementia. It also provides you with the opportunity to give positively to others in the community.

Home4All is always looking for new volunteers to assist us in creating happy days for our visitors with dementia. If you are interested in providing a happy day to those that have dementia, come and contact us at Jan@home4all.co.nz.

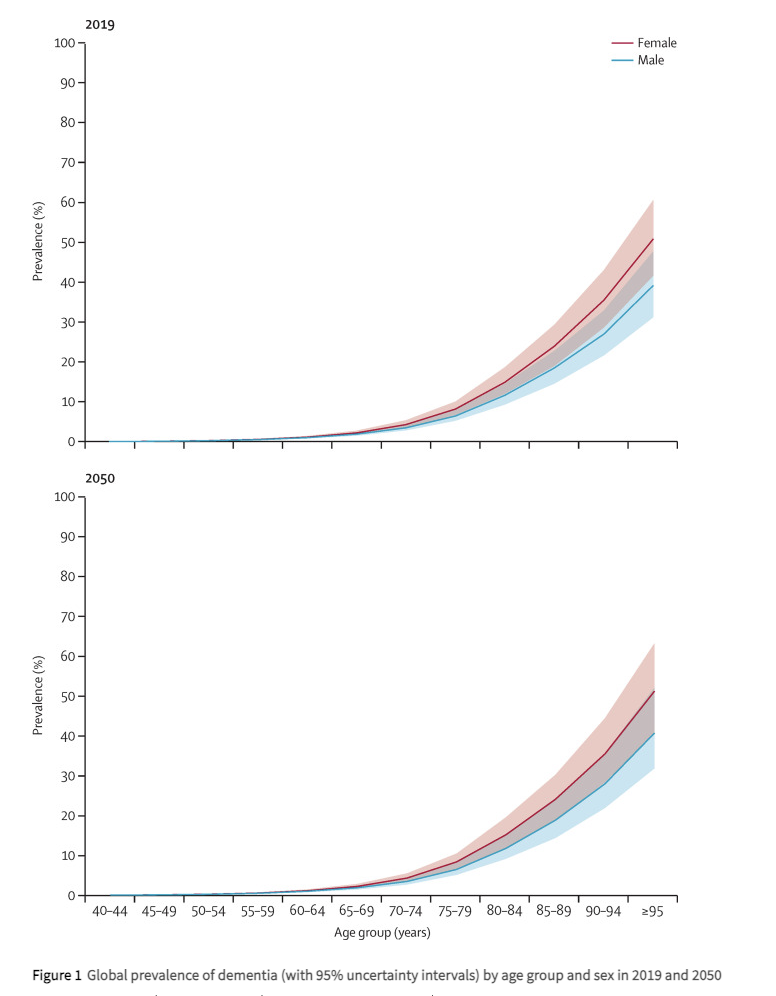

Below is a graph indicating the global prevalence of dementia by age group for male and female in 2019 and estimated figures for 20503.

![]()

Notes

1. For people aged between 65 and 69, around 2 in every 100 people have dementia. A person’s risk then increases as they age, roughly doubling every five years. This means that, of those aged over 90, around 33 in every 100 people have dementia (Source: Alzheimers.org.UK)

2. Griep Y, Hanson LM, Vantilborgh T, Janssens L, Jones SK, Hyde M. Can volunteering in later life reduce the risk of dementia? A 5-year longitudinal study among volunteering and non-volunteering retired seniors. PLoS One. 2017 Mar 16;12(3):e0173885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173885. PMID: 28301554; PMCID: PMC5354395.

3. GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022 Feb;7(2):e105-e125. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8. Epub 2022 Jan 6. PMID: 34998485; PMCID: PMC8810394.

At Home4All we focus on what you can do, rather than what you can't. It is all about creating happy days together with others, by doing the things you still can in a safe environment. We have a workshop, a vegetable garden, and animals to interact with. This short video provides an impression of some of our activities.

People living with dementia need their own government support budget

At the moment there is no government funding stream supporting this group of people. We saw this with one of the participants in the television programme "The restaurant that makes mistakes". A lady who was completely able to work in the kitchen under supervision lived in a rest home environment, where one of her biggest frustrations was that she was bored and was not able to do anything useful around the facility. It was a typical situation: too bad to stay at home alone but too good for a rest home. If she had been able to access funds that could support her staying longer at home and visiting an adult day activity centre, this would have made all the difference.

Let me introduce you to Donna[1]. Donna is a retired woman in her seventies who suffers from progressive cognitive decline/dementia and lives on her own at home. She has two sons, one who lives in New Zealand and the other in Europe. She can currently run her household but requires frequent support from her son.

Because of her cognitive decline, Donna forgets appointments and where she puts things. She is at the stage that she realises that she is forgetting, and so she frantically writes everything in her notebook in such a way that she is also unable to retrieve the information she put in it. Her finances are looked after by an agency that she visits several times per day as she forgets that she was there an hour earlier.

Three months ago, Donna came to Home4All (www.home4All.co.nz), and she spends two days per week with us. Home4All provides a safe environment for her where she does not need to be worried about what she might have forgotten. At Home4All she enjoys the company of others and can use her skills to help with the cooking and other activities around the home. This is what Donna enjoys and it gives her day meaning and fulfilment.

Unfortunately, Donna does not qualify for government support and has to pay out of her own pocket to come to Home4All. As a direct result, she has had to reduce her days coming to us from two to one day per week. As you can imagine, this again upsets her routine and puts her back into a situation full of uncertainty and social isolation.

People suffering from other neurodegenerative / life-limiting diseases are able to apply for financial support from the NZ government. This is not the case for people living with dementia / cognitive decline. We do not question whether people with cancer need support but we do for those living with dementia. Providing a variety of adult day activity programmes that enable those living with dementia to live meaningful and purposeful lives is important as it potentially reduces the slope of decline. In the UK, dementia is classified as a terminal illness[2] and therefore qualifies for the same level of care support as other life-limiting diseases receive.

Imagine if Donna could come three days per week to Home4All. We could monitor her level of decline and make sure there is appropriate care wrapped around her. We could make sure that her quality of life is as good as it can be before she dies a natural death or needs to be admitted into a care facility. Let’s not make people living with dementia wait to receive appropriate care. Give them their own care support budget to enable them to have a happy decline.

![]()

Notes

[1] To protect her identity, we changed her name.

[2] Social Care Institute for Excellence (https://www.scie.org.uk/)

Early signs of dementia manifest differently in everyone: you can pay attention to these 10 things

Anybody who gets a day older can confirm that not everything goes as smoothly as it did when they were eighteen. Physical activities become a bit slower to complete, you get tired a bit faster, and there is a little more mental wear and tear along the way. This is a normal part of getting older, according to various international Alzheimer's and dementia organisations. What is the difference when it comes to dementia? In other words, when is being forgetful no longer innocent?

Anybody who gets a day older can confirm that not everything goes as smoothly as it did when they were eighteen. Physical activities become a bit slower to complete, you get tired a bit faster, and there is a little more mental wear and tear along the way. This is a normal part of getting older, according to various international Alzheimer's and dementia organisations. What is the difference when it comes to dementia? In other words, when is being forgetful no longer innocent?

Problems in daily life

Dementia is not a normal ageing phenomenon, but the expression of a disease. The diagnosis is made when a doctor or specialist identifies a decline in mental abilities. The decline is such that the person has difficulty with daily activities, such as getting dressed or groomed independently, cooking food, or going to the store. You cannot prevent dementia, but you can partly limit your risk by living a healthy life. According to Dementia New Zealand around 70,000 people have dementia in this country.

Researchers have known for years that long before the first symptoms of dementia appear, damage can already be found in the brain tissue of (future) patients. The underlying disease is therefore often already present before there is a problem. In addition, the first symptoms are often so subtle that it takes a long time to realise that there may be more to it. Often years pass before someone is finally diagnosed with dementia.

Sometimes memory and cognitive tests show that there is indeed a decline in mental capacity that cannot be fully attributed to the normal ageing process. However these problems are often so mild that the person in question experiences few problems in practice. Doctors then speak of mild cognitive impairment. Although this is often seen as the pre-stage of dementia, it is certainly not the case that everyone with mild cognitive impairment will actually develop dementia.

Ten signs there's more to it

There are different types of dementia, each with typical and atypical symptoms. In addition, each individual has his or her own unique experience. There is no general definition of what the first stage of dementia looks like, but the following ten symptoms are the most common.

1. Severe memory problems

Quite normal

Not being able to think of a name occasionally or forgetting when an appointment was, such things are quite normal... especially if you can remember it a few hours later.

Suspicious

One of the typical early symptoms of Alzheimer's disease is forgetting new information. People with dementia can no longer do without a calendar or other aid to remember appointments or dates because they simply can no longer store that new information in their memory. Other omens include forgetting important dates or events and asking the same question over and over again.

2. Difficulty planning and problem solving

Quite normal

If you occasionally make a calculation error or overlook an invoice, you don't have to worry immediately. It is also not abnormal that you find it more difficult to do many things at the same time as you get older.

Suspicious

Executing complex plans, for example, with many calculations is difficult and requires much more concentration than before. Typical examples are getting stuck or making mistakes when cooking or baking a recipe that you have made (successfully) often in the past. It is also suspicious if you can no longer keep track of your finances and bills when you used to be able to do so without any problems.

3. Difficulties with familiar tasks

Quite normal

Needing help with technology or figuring out how to operate another new household appliance: these are no reason to panic.

Suspicious

If someone has trouble compiling a shopping list or forgets the rules of his or her favourite game, this could be an indication that problems are starting. Forgetting the way to a place where you have been for years is also not normal.

4. Being disoriented

Quite normal

Forgetting what day of the week it is. This happens to everyone sometimes.

Suspicious

People with dementia can sometimes become disoriented in time and space. For example, he or she no longer knows what season it is or whether something happened yesterday or last week. Forgetting where one is and/or how one got there can also be an early sign of dementia.

5. Misinterpreting visual information

Quite normal

Cataracts can be the cause of blurred vision in older people, but that has nothing to do with dementia.

Suspicious

Sometimes early dementia can manifest itself in problems with vision. This concerns difficulty in estimating distance, colour or contrast and can make it difficult to read, and especially to drive.

6. Language problems

Quite normal

Don't worry if you can't find the right word for a while, but find it later.

Suspicious

Those who are or become demented may experience problems following a (one-on-one) conversation or starting a conversation. He or she repeats himself or herself within the same conversation or abruptly stops talking. It is also possible that someone with (early) dementia cannot find the right word for normal things. Instead, he or she will use a wrong word or description, for example, "hand-clock" instead of watch.

7. Losing things and not being able to find them again

Quite normal

Losing your key or wallet, but being able to think in your mind where the item might be, is quite normal.

Suspicious

People with dementia sometimes put objects in an unusual place, for example, keys in the refrigerator. Moreover, when they lose something, they are no longer able to trace where they have been or where they last saw something in order to find it again. That is why it sometimes happens that people with dementia (often in a more advanced stage) start accusing others of stealing.

8. Poor estimation or judgement

Quite normal

We all make bad decisions from time to time, such as delaying a doctor's visit when we're not feeling well or not changing the oil in our car on time. In this case, it's more about procrastination than misjudgement of the situation.

Suspicious

A sign of dementia can be that someone is less able to assess the risks or consequences of his or her actions. This manifests itself in the handling of money, for example, in spending excessively. In the area of personal care, it happens that people with dementia wear too many warm clothes on a hot day, or no longer comb their hair, et cetera.

9. Taking less initiative

Quite normal

It is not unusual that those who get older also get tired faster and sometimes just don't feel like social obligations.

Suspicious

Difficulty remembering or following a conversation can make someone with early dementia more withdrawn. They may lose interest in their previous hobbies or passions. For example, it becomes too difficult to keep following the score in their favourite rugby match.

10. Mood and personality changes

Quite normal

Being in a bad mood from time to time when something goes wrong or sticking to your own routine and way of doing things is nothing to worry about.

Suspicious

When someone feels confused, depressed, anxious or restless for no apparent reason, this could be a sign of an underlying problem.

What should you do?

When you notice one or more signs of dementia in yourself or someone close to you, it can be very confrontational. People who work in local and international dementia organisations also realise this. It sometimes seems easier to dismiss concerns than to talk about them, especially if you're worried about someone else. You may be afraid of making him or her worried or angry. Nevertheless, it is important to discuss your concerns with the doctor, so that he or she can investigate the cause of the problems and possibly propose appropriate help.

![]()

Acknowledgement

The original of this article was written by Liesbeth Aerts and published on the 3rd of August in “Algemeen Dagblad”, a Dutch newspaper. It was translated with the support of Google Translate, after which small changes were made by Home4All staff to make it relevant for a New Zealand audience.