Admin

Add or change a family page

All news items:

When it comes to supporting people living with dementia in New Zealand today, day care centres play an important role. Their aim is usually twofold: to provide an engaging environment for visitors and to offer respite for their partners and/or full time care givers. This article focuses on the first aim: providing a stimulating environment.

What do people with dementia need?

People experiencing cognitive decline (dementia) tend to withdraw. They experience the world around them differently from others, and as a result are cautious to interact with people around them. They can become socially isolated which negatively affects their physical and mental health and general well-being. Day-care centres aim to reduce the impact of cognitive decline by providing social interaction, physical exercise and mental engagement. Most centres offer activities such as games, music, quizzes, storytelling, physical exercise, creative expression, eating together and the like.

The truth is, this model does not work for every person experiencing cognitive decline. People living with dementia want to live a purposeful life just like the rest of us which will vary from person to person. Some do like games or having a conversation, others prefer to be outside and be involved with day to day things as much as they are still able to.

Home4All wants to provide a model focusing on **empowering** people living with dementia. A recent study (1) identified four aspects important to empower people with cognitive decline / dementia:

- Having a sense of personal identity

- Having a sense of choice and control

- Having a sense of usefulness and being needed

- Retaining a sense of worth

Obviously these four aspects of empowerment can only be addressed taking into consideration the stage of cognitive decline the person is in.

At Home4All, our aim is to empower our visitors (people experiencing mild to moderate dementia) to use their lifelong skills, by engaging them in day-to-day activities they enjoy and can carry out with (or without) support from others. The ‘farm type’ environment consists of a large property (~200m2) set in a residential area with lawns, a flower garden, vegetable garden, large workshop (60 m2), several chickens and a dog. We support 8-10 people in their dementia journey and aim to give them the best experience of the week.

Ian – a problem solver, proud of his successes

Knowing and acknowledging who people are, empowers them to be confident in their identity. One of our visitors, Ian, is a born problem solver. Talk about a problem and he will immediately come up with solutions. For example, when we remove the nuts and bolts from the crossbars some of those are very hard to undo. Ian will always find a way to get it done and is ever so proud when he succeeds. A couple of these moments during the day let him go home with a smile on his face, telling us he had a good day.

Offering a choice is often challenging for people living with dementia. They do not want to make mistakes, as this is what they experience often in the early stage of cognitive decline. Presenting them with too many options creates confusion - it helps to narrow things down to a few more manageable choices for the person to choose from.

Kaye – choosing activities with happy memories

Why people make certain choices is not always clear from the get-go, but you might discover the reason along the way. One of our visitors, Kaye, is naturally cautious about making a choice if different options are presented. Recently I asked him to choose from a range of activities, one of them was digging a section of the vegetable plot. He is an 82-year-old fit gentleman and to my surprise he chose the digging. Digging is physically exerting, so we stayed close to make sure he was alright. After an hour he was still digging and appeared to enjoy himself. When I asked him why he enjoyed the digging (as he had an office job all his life), he mentioned it brought back happy memories of working as a child with his dad in the vegetable garden.

Having a sense of usefulness and being needed empowers people living with dementia. Like us, people living with dementia want to be useful to the people around them. Excluding them from activities that lie within their ability does not benefit their wellbeing. Especially normal day to day activities like laying the table and being involved in the washing up are a great way to make them experience reciprocity.

Chris* – an eye for detail and a sense of achievement

Activities that preserve their skills and talents is another great way to achieve this. Sometimes we need to encourage them, as they “forget” they still have those skills and talents. One of our visitors, an emeritus academic, took great satisfaction in ordering materials for the workshop like screws and bolts etc. This reflected his academic process in the past of ordering and analysing data and he applied his eye for detail to make sure the materials were exactly what was needed. He was very pleased to see everything neatly organised in one of the storage boxes - this gave him a great sense of achievement.

When it comes to the theme of retaining a sense of self-worth this is often challenged by their level of insecurity. People around them tend to take over and make decisions for those living with dementia. This can be frustrating and undermine their confidence.

Dave – feels valued for his mechanical skills

One of our visitors, Dave, was a mechanic all his life and loves to mess around with appliances and machines. When Dave comes to Home4All we try to have an appliance for him that he can take apart. While doing this, we notice that old skills and insights surface like asking for a special tool to do the job, a tool we had never even heard of. At the end we thank him for doing such a good job and confirm his expertise was needed to get the job done. When he goes home in the afternoon, he mentions he’s had a perfect day; although he does not remember exactly what he has done, he does remember feeling valued.

There are many more examples that we can give of our visitors responding positively to the environment we place them in. At Home4All we aim to create a natural “farm” type environment which provides a variety of activities visitors can choose from. The environment challenges them and provides them with self-worth and dignity. We only offer support when they need it and, miraculously, those occasions are far less than we expect. We know their dementia cannot be reversed but we can increase the level of satisfaction, self-worth and well-being of our visitors by empowering them.

![]()

Literature

- van Corven CTM, Bielderman A, Wijnen M, Leontjevas R, Lucassen PLBJ, Graff MJL, Gerritsen DL. Defining empowerment for older people living with dementia from multiple perspectives: A qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021 Feb;114:103823. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103823. Epub 2020 Nov 10. PMID: 33253930.

* Names have been changed to protect people’s privacy.

Lying awake for hours, tossing and turning, worrying, having satisfactory, pleasant and sufficient sleep is sometimes a problem for all of us, let alone someone with dementia, who recognizes their environment less and less, who exchanges day and night rhythm and has little to do during the day. But what exactly are sleeping problems, and how do you achieve good care?

Health Behavioural Registered Nurse Koen Manders has developed The Sleep Method, a step-by-step guide for a qualitatively better night's sleep.

One of the most important reasons for admission to a nursing home is issues with sleep: nocturnal restlessness, sleeping problems, or a caregiver who can no longer handle the care (at night). Unfortunately, sleeping medication, such as Temazepam, or a tranquilizer, such as Oxazepam, are still readily used. This has to change. The Dutch Care and Coercion Act* (abbreviated as WZD) also requires this.

One of the most important reasons for admission to a nursing home is issues with sleep: nocturnal restlessness, sleeping problems, or a caregiver who can no longer handle the care (at night). Unfortunately, sleeping medication, such as Temazepam, or a tranquilizer, such as Oxazepam, are still readily used. This has to change. The Dutch Care and Coercion Act* (abbreviated as WZD) also requires this.

It is known that sleep has a restorative function, both for the body and for brain activity. Cognitive processes, including memory and concentration, are given the chance to recover and 'reset'. Furthermore, it is not yet fully known what the purpose of sleep is. Three processes that affect sleep are:

- Biological clock (circadian rhythm): this nucleus in the hypothalamus regulates, through hormone levels, a recurrent structure of sleep and wake of approximately 24 hours.

- Sleep rhythm: sleep is not a fixed state, but a rhythm that lasts from 90 to 120 minutes, in which various brain activities take place. This can be roughly divided into deep sleep, light sleep and REM sleep (dream sleep).

- Sleep demand: The need for sleep increases during the day and decreases again during the night.

Long-term disruption of sleep can lead to many complaints. Symptoms such as cardiovascular disease, obesity, depression or anxiety can arise. It also affects one’s mood, concentration and memory reduced autonomy and independence can occur. If this happens occasionally, it likely isn’t cause for concern. If this is a regular occurrence, it may be an issue, especially if it is recurring for several nights in a row.

As age progresses, so-called gerontological changes occur in and around sleep:

- Biological clock (circadian rhythm): the hormone levels and body temperature linked to the sleep and wake cycle become less apparent. The number of consecutive hours of sleep at night decreases and the need for a nap during the day increases.

- Sleep rhythm: sleep becomes less deep, and sleep remains more in light sleep and REM sleep. There is also more change between the phases, and the rhythm is no longer constant.

- Sleep demand: demand builds up faster and is more difficult to release during the night.

Sleep hygiene

A good night's sleep starts during the day. A few tips to help achieve this are:

• A quiet and dark bedroom

• Keep screens (such as tablet, smartphone, television, etc) out of bedroom

• Make sure to only do relaxing activities, such as reading, at least an hour before bedtime

• Avoid caffeinated and alcoholic drinks several hours before bedtime

• Schedule a moment of worry during the day to come up with solutions to problems

• Refrain from eating heavy meals in the hours before bedtime

• Exercise regularly, but no later than three hours before bedtime

• Ensure an environment with sufficient light during the day

• Avoid naps or power naps during the day

• Try to get up at exactly the same time every day, even on weekends

The first intervention for sleeping problems is often the use of sleep medication. This entails many risks. The cognitive impairments as a result of dementia are additionally enhanced, as are daytime fatigue and an increased risk of falls. In addition, medication is also known to block the restorative functions of sleep, so that someone can relax, but this, for example, makes it more difficult to process difficult experiences. The Care and Coercion Act (WZD) has been developed to protect clients against unnecessary and unsafe use of these substances. The WZD regulates involuntary care for clients with dementia. This includes the use of behaviour-influencing medication and freedom restricting treatments , such as the closed door, bed rails or the weighted blanket. ?The basic principle is that the situation is looked at in a multidisciplinary way, whereby mainly sought for alternatives; is short terms: No… unless. ?

The search for alternatives is central to the WZD. Involuntary care may only be used if it can be demonstrated that sufficient alternatives have been investigated. But what are the alternatives? For the night, people often think of an extra low bed, or extra supervision, for example in the form of an infrared sensor, are sufficient, but there is no suitable guideline to answer these questions. Apart from sleep hygiene (see box), there is therefore no ready-made answer to sleeping problems. The night situation is different for everyone, including clients with dementia. This is why it is good to systematically search for suitable solutions geared to the individual patient’s needs.

The sleeping position

Everyone has a different position in bed. One prefers to sleep on their stomach, and another changes position every half hour. In hospitals, patients are traditionally placed on their backs in bed, so that the nurses can easily reach everything. Moreover, this is a healthy posture for the body. This preference of care employees is also reflected in home care or in a nursing home. That is what is taught in training. However, if someone has trouble changing their posture due to apraxia or physical problems, but prefers to sleep on their right side, it can be a long night.

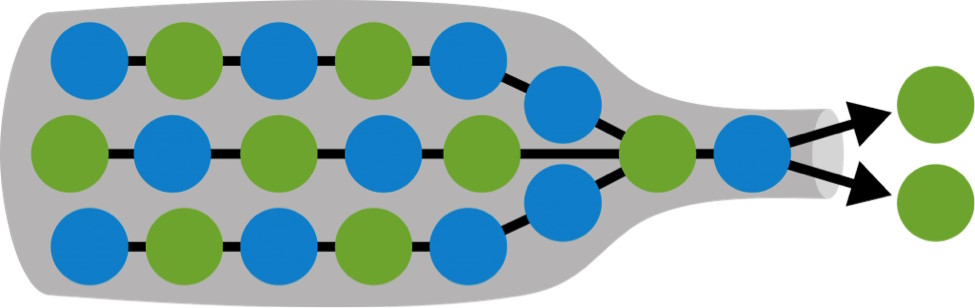

The Sleep Method is to help you find suitable solutions. It is a method that analyzes the sleeping situation on the basis of six steps and offers solutions to help the personal situation. Literature, studies and various practical experiences form the basis of the method, which bundles numerous interventions and divides them over the various steps. The method has been developed to offer alternative solutions. This gives care workers, informal caregivers and specialists a chance to look more broadly at the preferences of the client, and gives the opportunity to think of what might suit the individual client. In this way, customization and a person-oriented solution can be offered to the client with sleeping problems. The request from the WZD is also met with opportunities to take a broad look at alternatives and to only proceed with involuntary intervention only when these alternative options have been exhausted.

The sleep history is the basis of the sleeping method. In this first step, information is collected that can be used to identify which sleeping problems there are, and which solutions or interventions can be linked to these in the later steps. This is done, among other things, with a sleep/wake calendar, supplemented with questionnaires for the client, caregiver or care staff. This step is seen as a baseline measurement.

The sleep history is the basis of the sleeping method. In this first step, information is collected that can be used to identify which sleeping problems there are, and which solutions or interventions can be linked to these in the later steps. This is done, among other things, with a sleep/wake calendar, supplemented with questionnaires for the client, caregiver or care staff. This step is seen as a baseline measurement.

In step 2, we first look at various possible causes. Based on the information collected during the observation phase, together with the involved disciplines, such as occupational therapist, doctor and home care, we look at issues that may underlie poor sleep. These could be issues such as:

• Pain

• Itches

• Posture or discomfort

• Incontinence problems

• Sleep disorders

• Medication

Or any other number of physical causes.

This step, together with step 4, is the most important step within the Sleep Method. The aim is to look at the individual situation and to have it match the client's needs better. This is especially important, especially when admitted to a nursing ward, though it can also provide surprising solutions and ideas to the home situation. The sleeping climate and the preconditions can already be enough to stimulate a good night's sleep. These are a few things you may want to consider:

• Bedtime routines

• Bed linen and own pillow

• Nightwear

• Decoration and furniture of the room

• The temperature of the room. Elevated skin temperature is associated with drowsiness, deeper sleep and less frequent waking. This is why it is important to ensure you have a cool environment and warmth under the covers.

Every client is different, and the interventions are different for every client. This is why it is impossible to list all possible interventions. However, it is important to let go of one's own values and preferences and to look with an open mind at the client and their preferences, however small or strange they may be.

Alternative interventions include the use of signposting, dynamic stimuli, light therapy, day structure, and many other options that promote good sleep. In this step we look for appropriate interventions that can be added to the personal situation surrounding the client.

One form of a dynamic stimulus is a musical pillow. This pillow offers music or sound close to the head so that the client is distracted from sounds and ensures less of the desire to get up and be distracted by these sounds. The purpose of signage is to make it more visible where a client can find the toilet, for example. This can be done, for example, with illuminated arrows, or an image of the toilet on the outside of the bathroom door.

A recognizable daily rhythm is also important. A good variety of activity and rest matches the sleep needs of the elderly. In addition, this ensures recognisability and the client is less likely to withdraw or become bored.

If there is enough variety, an activity can also be offered in the evenings. A nice bath, something to eat while watching television or a game. This ensures that the time at which the older person goes to bed shifts and so does the time of waking up in the night. A win-win situation.

The last two steps concern the use of signals, and influence the freedom of movement or the use of sleep medication. With all these resources, it is important to take the considerations of the WZD into account and to compare these results. Sometimes a situation calls for the deployment of involuntary care, for example, if the client cannot find peace at night. Medication can sometimes offer a short-term solution, but also consider options that affect freedom of movement, such as a ball blanket, a tent bed, bed rails or an extra low bed. If a client cannot get out of bed by themself, the bed imposes a restriction. If a client cannot get up from the extra low bed, the complete step-by-step plan of the WZD must be followed, as this amounts to a restriction to the freedom of movement.

Sleep medication is only included in the method as a last resort. For some clients, this is a godsend, but there are few resources that actually offer better quality of sleep. The effect of medication is mainly to stun the client. Sleep medication can offer a temporary solution to, for example, stabilize the day and night rhythm again. That is why the means are mentioned and included in the sleeping method. Sleep medication always falls under the means that influence behaviour and the complete step-by-step plan of the WZD must always be followed for this to be taken into consideration.

While going through the steps, various disciplines can be consulted, such as an occupational therapist, family doctor, nurse and home care. The support of a dementia case manager / adviser can also help with this. They can all think along and supplement when you get stuck as a care professional, informal carer or client.

Author: Koen Manders

Website: www.kmconsulatatie.nl

kmconsulatatie@outlook.nl

Translation: Google, J. Weststrate, H. Cunningham

First published in: Denkbeeld February 2022

Picture: YUMMYBUUM/ADOBESTOCK

* Note: The Dutch Care and Coercion Act differs from the New Zealand legislation.

Bell mat

The bell mat is an example of a signal that can be used at night. This mat is available in different variants:

• in bed under the bottom sheet or under the mattress to receive a signal when the client moves more or less

• as a mat on the floor next to the bed. If the client stands on this, the care worker receives a signal. They can then consider whether the client needs assistance and offer guidance if necessary. This aid can also be used during the day when the client is sitting in a chair in his room.

“This is how I want to live if I were to develop dementia!” When I was young one of my favourite TV programmes was “Swiebertje”. When I have a dull moment nowadays I go and find an episode of “Swiebertje” on YouTube. Watching it brings me right back to the excitement I had watching it when I was 8 years old. I can still laugh about the funny situations and the hilarious conversations. Watching “Swiebertje” lifts my mood. I am definitely including it in my Dementia Passport.

“This is how I want to live if I were to develop dementia!” When I was young one of my favourite TV programmes was “Swiebertje”. When I have a dull moment nowadays I go and find an episode of “Swiebertje” on YouTube. Watching it brings me right back to the excitement I had watching it when I was 8 years old. I can still laugh about the funny situations and the hilarious conversations. Watching “Swiebertje” lifts my mood. I am definitely including it in my Dementia Passport.

Dementia passport

By Jan and Marian Weststrate

Yes, it is true that around 1 in 5 women, and 1 in 10 men will develop dementia at some point in their life (source Alz.org). In New Zealand one in four people die with this disease. This underscores the importance of being prepared and taking proactive steps to manage the condition.

One way to prepare for dementia is by creating a Dementia Passport in case you develop dementia. A Dementia Passport is a document that contains important information about you as a person. It focuses not so much on the medical side but much more on what you deem to be important in your life and enjoy, so that, if you develop dementia and are unable to communicate your preferences, the passport provides that information to those that care for you.

Your passport tells others what music you like; what your morning and evening routine is like; what conversations you enjoy (and don’t enjoy) and what television programmes you like to watch, particularly those ones when you were young. Next, is to list your favourite smell or which smells absolutely upset you (e.g. overripe bananas). It can also include how much you want to be involved with others and what time of the day you would like to be on your own. It is also important to include what embarrasses you, and what kind of situations you want to avoid. Don’t forget to include the type of books you like to read, or have read to you, when you are unable to read anymore. As you can see, you can add many aspects of your life to your Dementia Passport.

Creating a Dementia Passport can help ensure that when you develop dementia you receive appropriate person-centred care, even if you are unable to communicate your needs and preferences. Your passport can also help minimize confusion or misunderstandings among healthcare providers and caregivers, and can provide peace of mind to family members and loved ones.

To create a Dementia Passport, it is recommended to involve your loved ones and closest family. They probably know you better than anyone. You can always ask a dementia specialist to read it afterwards and ask him/her if it all makes sense. They can help ensure that the passport includes all relevant information and that it makes sense to others that do not know you. It is also important to keep your Dementia Passport up to date, and to review it regularly (e.g. yearly) as new things might pop up that you want included.

With one in five to ten people developing dementia, it is better to be safe than sorry on this topic.

Editorial note from Home4All

The Dementia Passport was initially suggested by Evelien Tonkens, professor of Citizenship and Humanization of the Public Sector at the University of Humanistic Studies in Utrecht, The Netherlands. She suggested this on 7/1/2007 in a column in The Volkskrant (a Dutch newspaper).

Marcel Canoy advocates socially oriented dementia care and breaking down the barriers to achieve this. According to Canoy, dementia is a gradual process for humans and a growing problem for society, or what he calls 'an economic sword of Damocles'. Each phase in the dementia process – from ‘not right’ to ‘fog’ – requires something different from the environment and care. What are those challenges and what barriers must be overcome?

Marcel Canoy advocates socially oriented dementia care and breaking down the barriers to achieve this. According to Canoy, dementia is a gradual process for humans and a growing problem for society, or what he calls 'an economic sword of Damocles'. Each phase in the dementia process – from ‘not right’ to ‘fog’ – requires something different from the environment and care. What are those challenges and what barriers must be overcome?

Beyond the system. Dementia as a mirror for integrated care.

Discussion on the inaugural lecture by Prof.Dr. M.F.M. Canoy, speech given at the acceptance of the position of professor by special appointment of Health Economics Dementia Care, on behalf of the VU University Special Chairs Foundation, at the request of the Gieskes Strijbis Fund, at the School of Business and Economics of VU University Amsterdam . Marcel Canoy gave the inaugural lecture on October 4, 2022.

What the speech is about?

In his inaugural lecture, Marcel Canoy advocates socially oriented dementia care and breaking down the barriers to achieve this. In 28 pages he presents his vision and the research plans of his chair Health Economics and Dementia. According to Canoy, dementia is a gradual process for humans and a growing problem for society, or an 'economic sword of Damocles'. Each phase in the dementia process - from 'not right' to 'fog' - requires something different from the environment and care. What are those challenges and what barriers must be overcome? That is what the speech is about.

In his inaugural lecture, Marcel Canoy advocates socially oriented dementia care and breaking down the barriers to achieve this. In 28 pages he presents his vision and the research plans of his chair Health Economics and Dementia. According to Canoy, dementia is a gradual process for humans and a growing problem for society, or an 'economic sword of Damocles'. Each phase in the dementia process - from 'not right' to 'fog' - requires something different from the environment and care. What are those challenges and what barriers must be overcome? That is what the speech is about.

An economic sword of Damocles

They are impressive numbers. The number of patients with dementia will double in the coming decades to more than 600,000 (estimates from the Netherlands). If nothing changes in the approach, this will require a doubling of the number of nursing home places in the next 20 years to more than 260,000 and of the number of care jobs to 700,000, while the number of informal carers per care recipient is falling from 5 to 3. The economist Canoy calls this an 'economic sword of Damocles'. And we know, more of the same won't work. But what, then?

The standard of care

Canoy is not only an economist, but also a painter. Using a few portraits, he shows how dementia develops and what needs to be done. The dementia care standard describes five phases: unsound, confusion, chaos, fog and finally, dying. The informal network and informal care is very important for the well-being of people with dementia when dealing with a gut feeling, increasing confusion and ever-growing chaos (which, for example, goes hand in hand with forgetting things). They continue to live at home as much as possible at this stage

At some point that is no longer possible: the chaos turns into fog. People can still be fine verbally, but the behaviour can be erratic, as can relationships with other people. Living at home has become very difficult but not living at home is also problematic.

Challenges

Each phase in the dementia process has different challenges and bottlenecks. Informal care and a person’s own network are important in every phase. Dementia care is largely something in the social domain. Canoy wants to investigate two questions: first, how we can improve the well-being of people with dementia and what this brings to society; and second, what prevents us from applying that improvement today. According to Canoy, three developments are important for improvements: a social, holistic approach aimed at customization; a social network; and the use of volunteers. He wants to investigate the impact of this approach, what kind of quality is required, (and how to measure it), and what the social costs and benefits are.

With the use of volunteers ('care seniors') you also remove the 'intergenerational imbalance' from the system (where fewer and fewer young people pay more and more, for more and more elderly people). You can use the potential (quantity and quality, editor) of 1.5 million 65 to 75-year-olds in this way

Bottlenecks and obstacles

The bottlenecks and obstacles to integrated approaches in our healthcare system have been mentioned more often. First of all, the incentives are wrong in a system where the provision of more (expensive) care generates more money than the non-delivery or less provision of (cheaper) care; or where the benefits of investments end up elsewhere other than the expenditure. We also are aware of the behaviour of shifting responsibilities between the various domains within and outside healthcare. Canoy points to good examples, such as the breakthrough method, or 1500 'caring communities', where barriers between the systems have been removed to the satisfaction of the citizens involved, and space has been created for initiatives by citizens themselves across the boundaries of the domains.

The bottlenecks and obstacles to integrated approaches in our healthcare system have been mentioned more often. First of all, the incentives are wrong in a system where the provision of more (expensive) care generates more money than the non-delivery or less provision of (cheaper) care; or where the benefits of investments end up elsewhere other than the expenditure. We also are aware of the behaviour of shifting responsibilities between the various domains within and outside healthcare. Canoy points to good examples, such as the breakthrough method, or 1500 'caring communities', where barriers between the systems have been removed to the satisfaction of the citizens involved, and space has been created for initiatives by citizens themselves across the boundaries of the domains.

The second category of obstacles is the fear of mistakes if care is provided outside one's own domain. Canoy calls this 'boarded-up protocol' a 'social straitjacket'. Canoy also wants to research these obstacles. How is it possible? What are the supply factors designed to support elderly people with dementia at home? Research into private financing is also appropriate here.

Caveats

Canoy provides a clear and concise overview of the challenges and obstacles in dementia care and support. Canoy's research program is comprehensive. The chair is called Health Economics, but the research questions are interdisciplinary. The research will certainly contribute to a better substantiation of the intended changes, which are also broadly pursued by the government. I would actually like to add three points of attention here.

The first is that we can and should always learn from our neighbours and from different cultures. The changes that Canoy is studying for the Netherlands are taking place all over the Western world. What can we learn from the similarities and differences in Europe? And how do various cultures in our own country deal with these challenges?

The second point for attention is that insight into benefits and costs, bottlenecks and obstacles, is necessary, but not a sufficient condition as an engine of change in a complex world. How do you bring about desirable changes in practice? How do the actors enter a change mode? For example, how do you nurture an army of "care seniors" or "breakthrough methodists"?

And finally, it would be nice if space was also found in the research projects themselves for the participation of informal carers, care seniors or experts by experience.

In short summary

As Canoy observes, the two main themes (social value and institutional obstacles to integrated dementia care) are linked when thinking about the future of long-term care. You can do two things with the challenges, says Canoy: either adjust the system so that we maintain as much as possible the solidarity between young and old, rich and poor, and higher and lower educated; or reduce health care and make people pay more themselves. If we don't choose the former, we choose the latter. Nobody wants that.

Editorial note Home4All

The purpose of sharing this article is to inform our New Zealand audience what is currently discussed in the Netherlands around the topic of dementia. What are the similarities when it comes to challenges and bottlenecks between our two countries? What in this article challenges our thinking? What thoughts come to the surface in our minds after reading this article? Where do you agree or disagree? Please share your thoughts with us via the contact form on our website.

This article is a translated version of the original article written by Leon Wever. Leon worked for a long time at the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport in the Netherlands. Starting out as a lawyer, he has held leadership positions in numerous policy areas. Since his retirement in 2020, he has been active as a supervisor, director and volunteer in, among other things, healthcare and legal protection. The article below was first published in “Nieuwsbrief zorg en innovatie” 30 March, 2023. The orginal title was: "Voorbij het systeem, dementiezorg als spiegel voor integrale zorg; Recensie van een oratie".

Translation: Google, Jan Weststrate and Hilary Cunningham

Since last year we have been fundraising to buy a Duo Bike as an addition to Home4All. This type of tandem bike enables two people to sit side by side while cycling and experiencing the different weather elements, whether it is sunshine, rain or wind. One person steers and both can pedal, supported by electric pedal support.

The Duo Bike (pictured) is produced by Van Raam, in the Netherlands. Most of the Green Care Farms have one or two on their premises. They also have developed a trailer that connects to the Duo Bike, which enables four people to enjoy a ride on the bike. This type of bike and trailer has all sorts of nifty gadgets that make it particularly possible for everyone to enjoy the ride.

The Duo Bike (pictured) is produced by Van Raam, in the Netherlands. Most of the Green Care Farms have one or two on their premises. They also have developed a trailer that connects to the Duo Bike, which enables four people to enjoy a ride on the bike. This type of bike and trailer has all sorts of nifty gadgets that make it particularly possible for everyone to enjoy the ride.

These types of bikes are expensive, especially with the electric pedal support. The funds for the Duo Bike have now been raised, yet we would love to continue raising funds to buy the trailer as well. If you would like to donate towards this project please check our “how we can help” page for the details.

Early emotional support for people living with early-stage dementia and their whanau is critical - according to a recent review of evidence-based support services.

The report, which was undertaken by Canterbury Psychiatrist Dr Matthew Croucher and others, highlights the need for more education and activities for people living with dementia and their whanau - to positively influence their quality of life.

The review, commissioned by Dementia New Zealand, will inform the future funding and delivery of services for the more than 70,000 people living with dementia in New Zealand of which the majority live at home.

“What happens next is a great opportunity to lift dementia care services from the bottom of the cliff to the top” says Dr Jan Weststrate Co-founder, with his wife Marian, of the Kapiti not-for-profit, Home4All.

“New Zealand is miles behind other countries, like the Netherlands, Australia and the US in the investment and the services it provides for people living with dementia. A recent study in the Netherlands shows just two planned support meetings shortly after someone is newly diagnosed, make a significant difference to the way people living with dementia and their whanau cope.”

In 2021 Dementia Wellington estimated that between 875 – 1400 people in Kāpiti currently live with the condition: about 700 are cared for at home. Numbers are likely to rise considerably because Kāpiti has one of the fastest growing aging populations in the country.

Dr Weststrate says support for newly diagnosed people and their whanau to talk more easily about their condition can make a real difference in reducing stigma around the condition. “Currently, permanent care is often the only available option. People need to be able to talk about the condition and get more help and support much earlier,” he says.

Jan and Marian Weststrate run Home4All, a Raumati Road day activity centre for people in the early stages of dementia. They promise ‘a happy day’ at their Green Care Farm - helping in the garden, art room and workshop, preparing lunch, meeting like-minded people and playing with Bella the dog.

Related links

• Download the NZ Dementia Foundation report here.

• Listen to the Radio NZ interview here.

Last September our garden chipper/shredder broke down while Erik, one of our Dutch friends, was visiting us. On arrival back in the Netherlands, without our knowledge, he organised a ‘give a little’ fund-raiser among friends and family. He raised NZ$1250 for a new garden chipper! When I was recently back in the Netherlands he gave me the cheque.

THANK YOU ERIK! AMAZING!

As an additional bonus, one of the people that donated remembered having worked in the 1970s with a Dutch guy in Africa, who moved to New Zealand. When we contacted him he had good connections with an agricultural machinery business and was happy to liaise with them to get us a good deal. A typical example of 1+1=3!

This is where the story text goes. Blah blah. This is where the story text goes. Blah blah.