Marcel Canoy advocates socially oriented dementia care and breaking down the barriers to achieve this. According to Canoy, dementia is a gradual process for humans and a growing problem for society, or what he calls ‘an economic sword of Damocles’. Each phase in the dementia process – from ‘not right’ to ‘fog’ – requires something different from the environment and care. What are those challenges and what barriers must be overcome?

Marcel Canoy advocates socially oriented dementia care and breaking down the barriers to achieve this. According to Canoy, dementia is a gradual process for humans and a growing problem for society, or what he calls ‘an economic sword of Damocles’. Each phase in the dementia process – from ‘not right’ to ‘fog’ – requires something different from the environment and care. What are those challenges and what barriers must be overcome?

Beyond the system. Dementia as a mirror for integrated care.

Discussion on the inaugural lecture by Prof.Dr. M.F.M. Canoy, speech given at the acceptance of the position of professor by special appointment of Health Economics Dementia Care, on behalf of the VU University Special Chairs Foundation, at the request of the Gieskes Strijbis Fund, at the School of Business and Economics of VU University Amsterdam . Marcel Canoy gave the inaugural lecture on October 4, 2022.

What the speech is about?

In his inaugural lecture, Marcel Canoy advocates socially oriented dementia care and breaking down the barriers to achieve this. In 28 pages he presents his vision and the research plans of his chair Health Economics and Dementia. According to Canoy, dementia is a gradual process for humans and a growing problem for society, or an ‘economic sword of Damocles’. Each phase in the dementia process – from ‘not right’ to ‘fog’ – requires something different from the environment and care. What are those challenges and what barriers must be overcome? That is what the speech is about.

In his inaugural lecture, Marcel Canoy advocates socially oriented dementia care and breaking down the barriers to achieve this. In 28 pages he presents his vision and the research plans of his chair Health Economics and Dementia. According to Canoy, dementia is a gradual process for humans and a growing problem for society, or an ‘economic sword of Damocles’. Each phase in the dementia process – from ‘not right’ to ‘fog’ – requires something different from the environment and care. What are those challenges and what barriers must be overcome? That is what the speech is about.

An economic sword of Damocles

They are impressive numbers. The number of patients with dementia will double in the coming decades to more than 600,000 (estimates from the Netherlands). If nothing changes in the approach, this will require a doubling of the number of nursing home places in the next 20 years to more than 260,000 and of the number of care jobs to 700,000, while the number of informal carers per care recipient is falling from 5 to 3. The economist Canoy calls this an ‘economic sword of Damocles’. And we know, more of the same won’t work. But what, then?

The standard of care

Canoy is not only an economist, but also a painter. Using a few portraits, he shows how dementia develops and what needs to be done. The dementia care standard describes five phases: unsound, confusion, chaos, fog and finally, dying. The informal network and informal care is very important for the well-being of people with dementia when dealing with a gut feeling, increasing confusion and ever-growing chaos (which, for example, goes hand in hand with forgetting things). They continue to live at home as much as possible at this stage

At some point that is no longer possible: the chaos turns into fog. People can still be fine verbally, but the behaviour can be erratic, as can relationships with other people. Living at home has become very difficult but not living at home is also problematic.

Challenges

Each phase in the dementia process has different challenges and bottlenecks. Informal care and a person’s own network are important in every phase. Dementia care is largely something in the social domain. Canoy wants to investigate two questions: first, how we can improve the well-being of people with dementia and what this brings to society; and second, what prevents us from applying that improvement today. According to Canoy, three developments are important for improvements: a social, holistic approach aimed at customization; a social network; and the use of volunteers. He wants to investigate the impact of this approach, what kind of quality is required, (and how to measure it), and what the social costs and benefits are.

With the use of volunteers (‘care seniors’) you also remove the ‘intergenerational imbalance’ from the system (where fewer and fewer young people pay more and more, for more and more elderly people). You can use the potential (quantity and quality, editor) of 1.5 million 65 to 75-year-olds in this way

Bottlenecks and obstacles

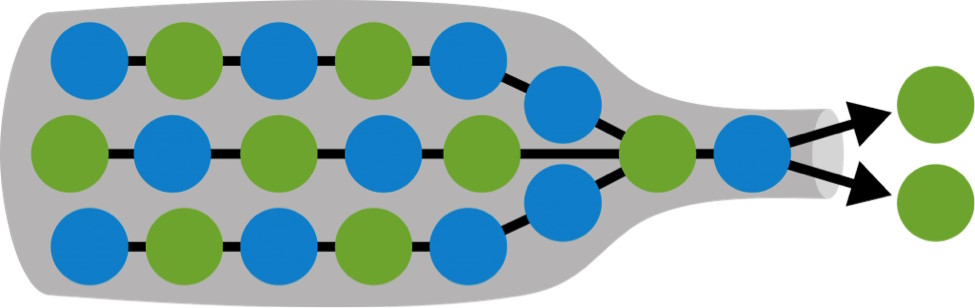

The bottlenecks and obstacles to integrated approaches in our healthcare system have been mentioned more often. First of all, the incentives are wrong in a system where the provision of more (expensive) care generates more money than the non-delivery or less provision of (cheaper) care; or where the benefits of investments end up elsewhere other than the expenditure. We also are aware of the behaviour of shifting responsibilities between the various domains within and outside healthcare. Canoy points to good examples, such as the breakthrough method, or 1500 ‘caring communities’, where barriers between the systems have been removed to the satisfaction of the citizens involved, and space has been created for initiatives by citizens themselves across the boundaries of the domains.

The bottlenecks and obstacles to integrated approaches in our healthcare system have been mentioned more often. First of all, the incentives are wrong in a system where the provision of more (expensive) care generates more money than the non-delivery or less provision of (cheaper) care; or where the benefits of investments end up elsewhere other than the expenditure. We also are aware of the behaviour of shifting responsibilities between the various domains within and outside healthcare. Canoy points to good examples, such as the breakthrough method, or 1500 ‘caring communities’, where barriers between the systems have been removed to the satisfaction of the citizens involved, and space has been created for initiatives by citizens themselves across the boundaries of the domains.

The second category of obstacles is the fear of mistakes if care is provided outside one’s own domain. Canoy calls this ‘boarded-up protocol’ a ‘social straitjacket’. Canoy also wants to research these obstacles. How is it possible? What are the supply factors designed to support elderly people with dementia at home? Research into private financing is also appropriate here.

Caveats

Canoy provides a clear and concise overview of the challenges and obstacles in dementia care and support. Canoy’s research program is comprehensive. The chair is called Health Economics, but the research questions are interdisciplinary. The research will certainly contribute to a better substantiation of the intended changes, which are also broadly pursued by the government. I would actually like to add three points of attention here.

The first is that we can and should always learn from our neighbours and from different cultures. The changes that Canoy is studying for the Netherlands are taking place all over the Western world. What can we learn from the similarities and differences in Europe? And how do various cultures in our own country deal with these challenges?

The second point for attention is that insight into benefits and costs, bottlenecks and obstacles, is necessary, but not a sufficient condition as an engine of change in a complex world. How do you bring about desirable changes in practice? How do the actors enter a change mode? For example, how do you nurture an army of “care seniors” or “breakthrough methodists”?

And finally, it would be nice if space was also found in the research projects themselves for the participation of informal carers, care seniors or experts by experience.

In short summary

As Canoy observes, the two main themes (social value and institutional obstacles to integrated dementia care) are linked when thinking about the future of long-term care. You can do two things with the challenges, says Canoy: either adjust the system so that we maintain as much as possible the solidarity between young and old, rich and poor, and higher and lower educated; or reduce health care and make people pay more themselves. If we don’t choose the former, we choose the latter. Nobody wants that.

Editorial note Home4All

The purpose of sharing this article is to inform our New Zealand audience what is currently discussed in the Netherlands around the topic of dementia. What are the similarities when it comes to challenges and bottlenecks between our two countries? What in this article challenges our thinking? What thoughts come to the surface in our minds after reading this article? Where do you agree or disagree? Please share your thoughts with us via the contact form on our website.

This article is a translated version of the original article written by Leon Wever. Leon worked for a long time at the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport in the Netherlands. Starting out as a lawyer, he has held leadership positions in numerous policy areas. Since his retirement in 2020, he has been active as a supervisor, director and volunteer in, among other things, healthcare and legal protection. The article below was first published in “Nieuwsbrief zorg en innovatie” 30 March, 2023. The orginal title was: “Voorbij het systeem, dementiezorg als spiegel voor integrale zorg; Recensie van een oratie”.

Translation: Google, Jan Weststrate and Hilary Cunningham